Asymmetric cell division in C. elegans

Asymmetric cell division occurs when one cell gives rise to two daughter cells with distinct cellular fate, function and, sometimes, different size. Asymmetric division is found in many organisms: from yeast, bacteria, fly to higher vertebrates. This process has been extensively studied, as it is fundamental to generate cell lineage diversity and specialized functions in multicellular organisms. Research on model organisms like C. elegans has contributed to the current understanding on how asymmetric division is regulated.

Ultra fast temperature shift device for in vitro experiments under microscopy

Asymmetric division and cell lineage diversity

The main mechanisms generating asymmetric cell division are: 1) asymmetric distribution of cell components (cell fate determinants) in the daughter cells and 2) asymmetric localization of daughter cells relative to external factors (e.g. signaling from neighbour cells) (Morrison and Kimble 2006).

This process is central to mammalian development. Stem cells (like neural or epidermal progenitors) can divide asymmetrically, allowing for self-renewal and creation of a progeny of differentiated daughters. Importantly, the balance between asymmetric and symmetric stem cell division is required during injury and disease (Morrison and Kimble 2006).

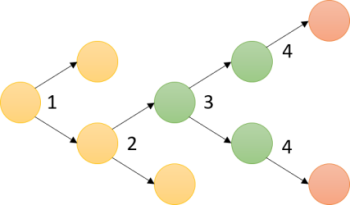

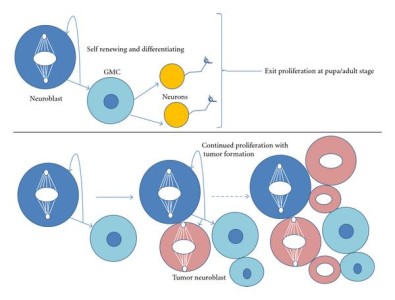

The molecular mechanisms leading to asymmetric division have been deciphered in model organisms like the worm C. elegans and the fly D. melangaster (Gönczy 2008). Pioneer discoveries in Drosophila allowed to identify Numb as the first asymmetrically distributed cell fate determinant. One well studied example of asymmetric division during Drosophila development is brain development, with neurons in the larval stages generated from asymmetric division of neuroblasts, which divide in a stem-cell like manner (though self-renewal and cell fate determination, see figure). Another example is the generation of external sensory organs in Drosophila through asymmetric divisions from a single precursor cell SOP (sensory organ precursor). The following lecture from J. Knoblich (IMBA, Vienna) illustrates these examples in model organisms:

Asymmetric division during C. elegans development

With its perfectly documented cell-lineage development, C. elegans is a model of choice to study asymmetric cell division. A succession of asymmetric divisions during the development of the worm ensures the establishment of the organism anterior/posterior, dorso/ventral and left/right axes.

In his review (Li, 2013), R.Li explains that there are three requirements for asymmetric division to take place: segregation of cell fate determinants (RNA transcripts, cell polarity proteins), chromosome repartition in the two daughter cells, and cell division itself. Before division, cell fate determinant factors are unequally localized to the cell poles of the mother cell, establishing cell polarization. Of the polarized poles will depend spindle orientation and the orientation of the cell plane division. When cytokinesis occurs, cell determinants are inherited by only one of the two daughter cells, which will then adopt a distinct cellular fate from its mother.

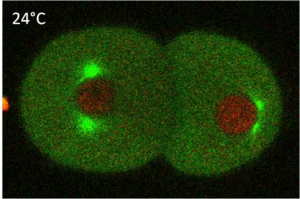

Experimental approaches to study asymmetric division in C. elegans development using temperature sensitive mutants

C. elegans embryos are large and immotile, what makes them particularly suitable for live cell imaging. Additionally, a large collection of temperature-sensitive mutants (ts) is available. JG White’s group (O’connell et al., 1998) used a genetic screen to identify temperature-sensitive cell-division mutants in C. elegans, defective for spindle-orientation, cytokinesis, or had abnormal microtubule organization. These ts mutants have been an invaluable tool to decipher the molecular pathways controlling asymmetric division.

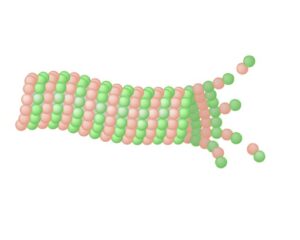

The use of ts mutants requires shifting C. elegans from a permissive to a restrictive temperature, allowing for an inducible and reversible protein inactivation. CherryTemp is a temperature controller which allows to shift the temperature of entire worms in seconds, allowing for the observation of rapid downstream effects while live imaging the embryo. Increasing or decreasing the temperature at the sample in a very controlled manner allows to generate hypomorhic-controlled activity of temperature-sensitive proteins.

References

- SJ. Morrison, J.Kimble, Asymmetric and symmetric stem-cell divisions in development and cancer, Nature, 2006 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16810241

- P. Gönczy. Mechanisms of asymmetric cell division: flies and worms pave the way, Nature reviews, 2008 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18431399

- R. Li ,The Art of Choreographing Asymmetric Cell Division, Dev cell, 2013 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23763946

- LS. Rose P. Gönczy Asymmetric cell division and axis formation in the embryo, WormBook 2005 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18050411

- NW Goehring, PK Trong, JS Bois, D Chowdhury, EM Nicola, AA Hyman, Grill SW. Polarization of PAR proteins by advective triggering of a pattern-forming system, Science, 2011 http://science.sciencemag.org/content/334/6059/1137

- CR.Cowan, AA. Hyman. Asymmetric cell division in C. elegans: cortical polarity and spindle positioning. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2004. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15473847

- KF. O’Connell, CM. Leys and JG. White. A Genetic Screen for Temperature-Sensitive Cell-Division Mutants of Caenorhabditis elegans genetics 1998 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1460235/

FAQ

Asymmetric cell division is a process observed when one cell divides to produce two daughter cells that have distinct cellular fates and functions. The resulting daughter cells may also be different in size. This mechanism is considered essential for generating cell lineage diversity. It also creates specialised functions in multicellular organisms. The process is found in many types of organisms, including yeast, bacteria, flies, and higher vertebrates. In mammals, this type of division is central to development. For example, stem cells, such as neural progenitors, can divide asymmetrically. This allows for both self-renewal of the stem cell and the creation of a progeny of differentiated daughter cells.

Two main mechanisms are described that generate asymmetric cell division. The first mechanism is the asymmetric distribution of cell components within the daughter cells. These components are also known as cell fate determinants. The second mechanism involves the asymmetric localisation of the daughter cells. This localisation is relative to external factors. An example of such an external factor is signalling that comes from neighbour cells. Research in model organisms like C. elegans and D. melanogaster has helped to decipher the molecular mechanisms involved. For instance, Numb was identified in Drosophila as the first asymmetrically distributed cell fate determinant.

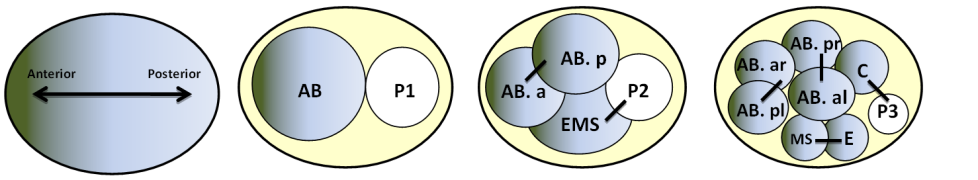

A succession of asymmetric divisions during the development of the worm ensures the establishment of the organism’s axes. The very first cellular division in the embryo is asymmetric. This process begins at fertilisation. The sperm centrosome is pushed towards one side of the embryo. This position defines where the first mitotic spindle will be and also sets the division site. At the end of this first division, the anterior-posterior axis is organised. The originally symmetric P0 embryo is partitioned into a larger anterior blastomere (AB) and a smaller posterior one (P1). The dorso-ventral axis is defined during the second division by EMS and Abp. Finally, the left-right asymmetry is set up at the end of the third division.

PAR proteins have an important function in the determination of cell polarity. In C. elegans mutants for PAR, a loss of anterior-posterior polarity was observed, along with defective cell fate destiny. Before the first division of the embryo, these PAR proteins are distributed equally at the cell cortex. Their repositioning is necessary for establishing polarity. This repositioning is facilitated by flows of the cortical acto-myosin network. This same acto-myosin network is also needed for positioning the sperm centrosome, which occurs before the first division. Before division occurs, cell fate determinants like polarity proteins are unequally localised to the cell poles, establishing cell polarization. The orientation of the cell division plane will depend on these polarized poles.

C. elegans embryos are suitable for live-cell imaging because they are large and immotile. A large collection of temperature-sensitive (ts) mutants is also available for this organism. These mutants have been an invaluable tool for deciphering the molecular pathways that control asymmetric division. For instance, a genetic screen was used to identify ts cell-division mutants that were defective for spindle-orientation, cytokinesis, or had abnormal microtubule organisation. The use of these ts mutants involves shifting the worms from a permissive temperature to a restrictive one. This temperature shift permits an inducible and reversible inactivation of the protein being studied. This allows for the observation of rapid downstream effects while the embryo is being imaged.