Introduction

Extremophilic organisms are capable of growth in extreme environments. Thermophiles are adapted to high temperatures (up to 122°C) while cryophiles (or psychrophiles) live at low temperatures (down to -20°C). Some of these organisms are obligate thermophiles, thriving at extreme temperatures, while others are thermotolerant although with suboptimal growth.

Ultra fast temperature shift device for in vitro experiments under microscopy

Thermophile and cryophile adaptation to extreme temperatures

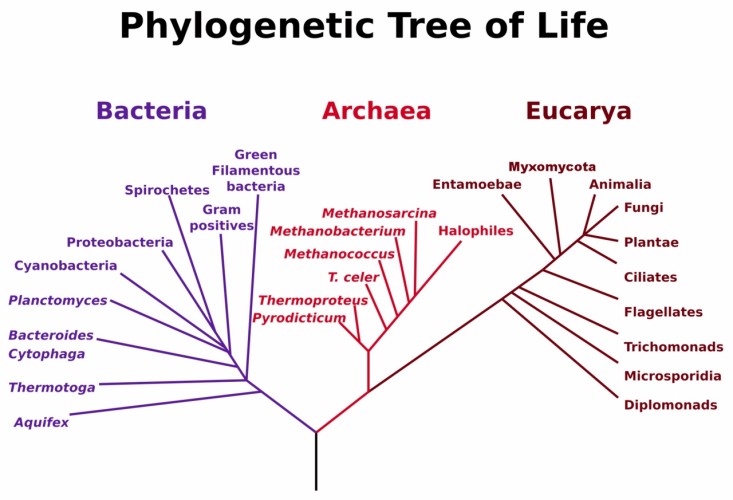

Extreme cold and hot environments are ubiquitous on Earth, occupying a big surface of the planet, despite these habitats are incompatible with many forms of life (mesophile organisms, with optimal growth between 20°C and 45°C). However, extremophile species have been identified in the three domains of life, including animals and plants. Thermophile and cryophile archaea and bacteria are extremophiles adapted to temperature but as well to other factors linked to their extreme habitats, like pH, presence of ice, desiccation or high pressure.

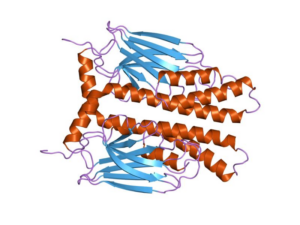

One example of evolutionary thermal adaptation is modification of membrane lipid composition. Stability of bilayer membrane and membrane permeability must be maintained at high temperatures and this is achieved by the modification of the percentages of different lipids. Membrane lipid composition is a main difference between archaea and bacteria (2). This makes their mechanisms for membrane adaptation to temperature different. While thermophile archaea keep membrane functionality at the whole range of temperatures through their unique isoprenoid chains, thermophilic bacteria show modifications in the fatty acid composition according to temperature (1). Additional examples of thermal adaptation are: amino acid composition leading to thermal stability of proteins (3), number of ORFs encoding for heat shock proteins and chaperones, specialized DNA repair systems (4), and genome size (5).

Additionally, horizontal gene transfer has been shown to play an important role in the evolutionary adaptation of thermophiles to extreme conditions, providing an additional level of genome plasticity. Horizontal gene transfer can occur between species of different domains (6, 7).

With the advent of transcriptomics and sequencing technologies, major contributions in the understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying bacterial adaptation to hot and cold have been made (8). Metagenomic analyses don’t require laboratory culture and have revealed: 1) the biodiversity in microbial communities adapted to specific environments and 2) habitat-linked genomic features (9).

Thermophile archaea and bacteria are the source of very important tools for molecular biology, like the historical discovery of the Taq DNA polymerase widely used for PCR. Nowadays, the knowledge and use of these species, with their unique metabolic and enzymatic activities, is key for the development of multiple industrial and biotechnological applications (4). Industrial processes with reduced environmental impact are of growing interest for a sustainable economic growth. In this context, Cryophiles are used as a source of cold-active enzymes and biosurfactants, which can be produced in a cold (low environmental impact) manner and may replace chemical surfactants in the food industry, detergent production or pharmaceutical industry (11). Thermophiles are also of industrial interest: the archaea Sulfobolus, for instance, has been used as a source of enzymes and metabolites of interest in the food, textile and pharmaceutical industries because of their thermal stability (10).

References

- [1] Koga Y. Archaea (2012) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22927779

- [2] Samta J et al, Front Microbiol (2014) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4244643/

- [3] Zeldovich et al. PLoS Comput Biol (2007) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17222055

- [4] Urbieta MS et al. Biotechnol Adv. (2015) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25911946

- [5] Sabath N. et al. Genome Biol Evol. 2013; 5(5):966-77

- [6] Schoenfeld TW et al., Mol Biol Evol. (2013) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23608703

- [7] Kumwenda et al. BMC Genomics. (2014) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4180962/

- [8] Walther J.et al. 2010. Archaea. (2011) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21350598

- [9] Cowan DA et al., Curr Opin Microbiol. (2015) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26048196

- [10] Quehenberger J et al. Front Microbiol (2017) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/m/pubmed/29312184/

- [11] Perfumo A. et al. Trends Biotechnol. (2018)

- [12] Yellowstone Resources and Issues Handbook, 2017, p.132

FAQ

Extremophilic organisms are defined by their capability for growth in extreme environments. Organisms that are adapted to high temperatures, up to 122°C, are called thermophiles. In contrast, organisms that live at low temperatures, down to \-20°C, are known as cryophiles or psychrophiles. Some of these organisms are obligate thermophiles, meaning they thrive at these temperatures. Others are described as thermotolerant, and they exhibit suboptimal growth in these conditions. Extreme hot and cold environments are ubiquitous on Earth. While these habitats are incompatible with mesophile organisms, which grow optimally between 20°C and 45°C, extremophile species have been identified in all three domains of life.

One example of evolutionary thermal adaptation is the modification of membrane lipid composition. The stability and permeability of the bilayer membrane must be maintained at high temperatures. This is achieved by modifying the percentages of different lipids. A primary difference between archaea and bacteria is their membrane lipid composition. This distinction means their mechanisms for temperature adaptation are also different. Thermophile archaea, for example, keep their membrane functional across the whole range of temperatures by using their unique isoprenoid chains. Thermophilic bacteria, however, show modifications in their fatty acid composition based on the surrounding temperature.

In addition to membrane lipid changes, other examples of thermal adaptation are noted. These include the amino acid composition of proteins, which leads to their thermal stability. The number of ORFs encoding for heat shock proteins and chaperones is another mechanism. Specialized DNA repair systems and variations in genome size are also listed as adaptations. Furthermore, horizontal gene transfer has been shown to be a consequential factor in the evolutionary adaptation of thermophiles. This process provides an additional level of genome plasticity. Horizontal gene transfer can occur between species that belong to different domains.

Thermophile archaea and bacteria are the source of valuable tools for molecular biology, such as the Taq DNA polymerase used for PCR. The understanding and use of these species, with their unique metabolic and enzymatic activities, is central to the development of multiple industrial applications. Industrial processes with a reduced environmental impact are receiving increasing attention for sustainable growth. In this area, cryophiles are used as a source of cold-active enzymes and biosurfactants. These can be produced in a cold, low-impact manner. They may replace chemical surfactants in the food industry, detergent production, or the pharmaceutical industry. Thermophiles are also valued by industry. The archaea Sulfobolus, for instance, is used as a source of enzymes and metabolites in the food, textile, and pharmaceutical industries because of their thermal stability.