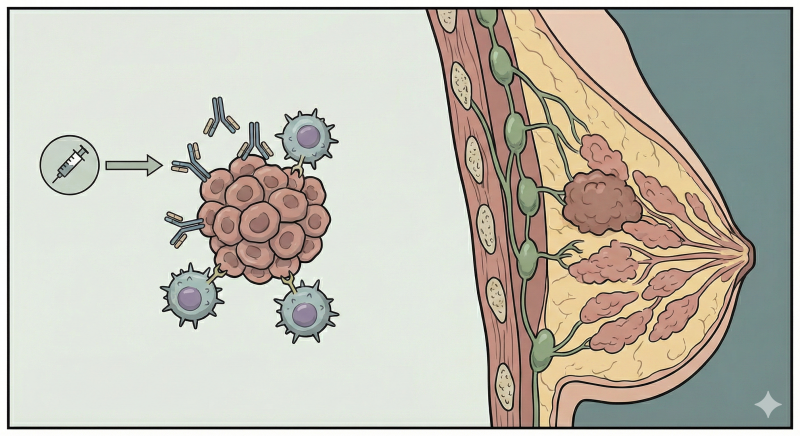

In oncological research, the development of a 3D model for breast cancer immunotherapies marks a pivotal shift from traditional preclinical testing. While immune-based interventions have radically altered the prognostic landscape for hematological malignancies, their efficacy in solid tumors, such as breast carcinoma, remains paradoxically inconsistent. To bridge this translational gap, researchers are moving beyond flat, two-dimensional cultures, turning instead to bioengineered three-dimensional systems. By meticulously recapitulating the architecture of the tumor microenvironment, these advanced platforms, ranging from patient-derived organoids to microfluidic tumor-on-chip devices, offer an unprecedented lens into immune-tumor dynamics. They promise not only to unravel the mechanisms of resistance but to accelerate the design of more potent, personalized immunotherapeutic strategies.

Learn more about our ready to use breast cancer organoid models.

The problem with immunotherapies in solid tumors

To understand the urgent necessity of advanced modeling in breast cancer research, one must first appreciate the dichotomy of current immunotherapeutic success. The field witnessed a paradigm shift with the advent of therapeutic T cell engineering, particularly the development of Chimeric Antigen Receptors (CARs).

These synthetic receptors reprogram lymphocyte specificity, effectively creating “living drugs” capable of recognizing surface antigens independent of the Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC). In the realm of “liquid” tumors (specifically B-cell leukemias and lymphomas) therapies targeting CD19 have demonstrated remarkable potency, inducing complete remission rates that were previously unimaginable in refractory patients.

However, translating this “liquid” success to solid malignancies like breast cancer has proven to be a formidable challenge. Unlike hematological cancers, where targets are readily accessible within the bloodstream and lymphatic system, solid tumors present a hostile, fortified landscape. The transition from treating blood cancers to solid tumors exposes critical bottlenecks: trafficking, infiltration, and the immunosuppressive nature of the Tumor Microenvironment (TME).

In breast cancer, for a therapeutic T cell or Natural Killer (NK) cell to be effective, it must first successfully navigate the vasculature and extravasate into the tissue. This process is often hindered by aberrant tumor angiogenesis.

Once in the tissue, these effector cells face a physical fortress. The desmoplastic stroma, characteristic of many breast carcinomas, acts as a mechanical barrier, physically excluding immune cells from making contact with malignant cells. Furthermore, the TME is metabolically hostile; characterized by hypoxia, nutrient deprivation, and oxidative stress, it drives infiltrating T cells toward a state of dysfunction and exhaustion.

Compounding these physical and metabolic barriers is the issue of tumor heterogeneity. Unlike the uniform expression of targets often seen in experimental models, human breast tumors are mosaics of antigen expression. This heterogeneity allows antigen-negative variants to escape immune surveillance, leading to treatment failure and relapse.

Traditional preclinical models have largely failed to capture this complexity. Two-dimensional (2D) cell cultures cannot replicate the mechanical pressures, chemical gradients, or spatial organization of the TME. Similarly, while murine models provide systemic context, significant interspecies differences in immune physiology limit their predictive power for human responses.

This is where 3D microphysiological systems offer a transformative opportunity. By generating spheroids, Patient-Derived Organoids (PDOs), and tumor-on-chip systems, researchers can now visualize the “battlefield” with high fidelity. These models allow for the precise observation of T cell recruitment and the interrogation of how immune cells navigate the physical stroma. They enable the study of intravasation (the entry of tumor cells into vessels) providing insights into metastatic progression. Crucially, utilizing PDOs allows for personalized screenings, matching specific CAR constructs or bispecific antibodies to a patient’s unique tumor architecture. By modeling the TME in three dimensions, we can finally dissect the mechanisms of immune exclusion and exhaustion, paving the way for the next generation of solid tumor therapies.

Spheroids and organoids for recapitulating tissue complexity

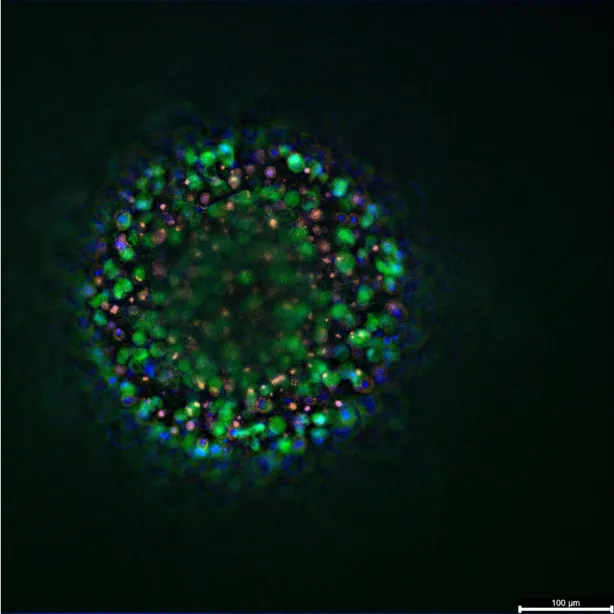

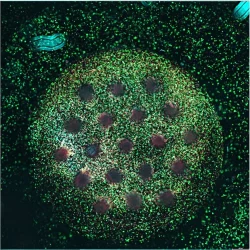

Spheroids (aggregates of immortalized cell lines) and Patient-Derived Organoids (PDOs) represent a critical advancement in preclinical testing, offering a physiologically relevant platform that captures the structural and functional heterogeneity of breast tumors. Unlike monolayer cultures, these three-dimensional models develop distinct metabolic gradients characterized by a proliferating rim and a necrotic, hypoxic core that impose physical and chemical barriers similar to those found in vivo. This architecture is essential for evaluating the functional capacity of immunotherapies beyond simple cytotoxicity. These models allow researchers to assess critical logistical challenges, such as the kinetics of immune cell trafficking, the ability of effector cells to penetrate the dense extracellular matrix (ECM) versus stalling at the periphery, and the stability of the immunological synapse under metabolic stress. Furthermore, PDOs facilitate a personalized medicine approach; by expanding tumor tissue from biopsies, clinicians can screen various CAR constructs or antibody formats against a patient’s specific tumor profile, identifying potential resistance mechanisms like antigen shedding or stromal exclusion prior to clinical application.

For instance, bispecific antibodies (bsAbs) can be investigated to determine how they initiate immune responses within a dense tissue matrix, as shown by Liao et al. (2024). In their high-throughput screening of ECM-embedded BT474 breast cancer tumoroids, the researchers discovered that efficacy in 3D relies on specific molecular mechanics that are invisible in 2D assays. While multiple bsAb constructs showed promise in monolayer cultures, the 3D model revealed that only those binding to membrane-proximal epitopes of HER2 could trigger a necessary “wave” of paracrine signaling. This signaling was crucial for actively recruiting T cells from the surrounding matrix into the tumoroid; constructs targeting distal epitopes failed to initiate this recruitment, rendering them ineffective in the 3D setting despite high binding affinity(1).

Similarly, Warwas et al. (2021) utilized MCF-7 spheroids to demonstrate that overcoming the physical density of breast tumors often requires “split co-stimulation.” They found that standard engagement of T cells via CD3 alone was insufficient to drive deep tissue infiltration. However, by introducing a second bispecific antibody to simultaneously engage the co-stimulatory receptor CD28, they achieved robust T cell activation and tumor destruction. This highlights the utility of spheroids in identifying the threshold of signaling required to breach the physical defenses of solid tumors(2).

Also, CAR NK and T cells can be studied to understand how physical constraints and evolved resistance mechanisms impact cellular therapy, as illustrated by Cho et al. (2024)(3). Using a microwell array to immobilize BT474 spheroids, they quantified the impact of tumor dimensions on immune efficacy. Their data showed that larger spheroids generated significant hypoxic cores that actively suppressed CAR T cell cytotoxicity and the secretion of effector cytokines like IFNℽ and TNFɑ. Crucially, they established the “initial CAR T cell to spheroid area ratio” as a predictive metric for therapeutic success, providing a quantitative framework for dosing strategies that is impossible to derive from 2D models.

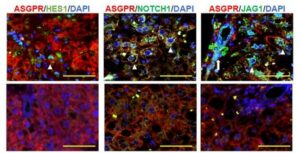

Furthermore, Röder et al. (2025) demonstrated the power of organoids in modeling drug resistance. Utilizing a genetically engineered mouse-derived organoid model (CKP) of ErbB2 (HER2)-positive breast cancer, they replicated the process of Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition (EMT), a cellular state associated with high metastatic potential and resistance to standard chemotherapy. The study revealed that while these aggressive, mesenchymal-like organoids were refractory to conventional drugs, they remained highly sensitive to killing by ErbB2-targeted CAR-NK cells. This finding validates the use of organoids as a rigorous testing ground for immunotherapies aimed at the most refractory and aggressive breast cancer phenotypes(4).

Breast cancer-on-chip models: A next-generation platform for mechanistic immunotherapy evaluation

Breast cancer-on-chip systems expand the analytical capabilities of 3D tumor models by introducing vascular perfusion, spatial compartmentalization, controlled biochemical gradients, and continuous imaging. These platforms reproduce essential features of breast tumors including endothelial barriers, stromal organization, nutrient asymmetries, and directional immune-cell trafficking while allowing precise manipulation of the microenvironment. As a result, they enable researchers to probe mechanisms that remain inaccessible to spheroids or organoids alone, such as the dynamics of immune infiltration, the emergence of stromal resistance, and the evolution of immunotherapeutic potency under physiologic stress.

One of the earliest demonstrations of this utility came from microfluidic systems designed to model immune checkpoint blockade. In the cancer-on-chip platform developed by Jiang et al., breast cancer spheroids (MDA-MB-231) were co-cultured with perfused T cells in an array of miniaturized bioreactors. The design allowed direct quantification of T-cell infiltration and IL-2 secretion in response to anti–PD-1 treatment, revealing that checkpoint inhibition restored T-cell function only in tumors with sufficient PD-L1 expression(5). These results underscore how microfluidic control over immune–tumor interactions can expose biomarkers of responsiveness that are crucial for precision oncology.

Building on this, Ayuso et al. introduced a breast tumor-on-a-chip containing a perfused endothelial lumen adjacent to a 3D MCF-7 tumor region, thereby generating realistic gradients of oxygen, nutrients, and acidity. When NK cells were introduced through the vascular surrogate, they initially migrated into the tumor and exerted cytotoxic effects, but the progressively hostile environment induced profound and persistent NK-cell exhaustion even after removal from the chip(6). This finding illustrates how on-chip systems can reveal temporal immune dysfunction driven by microenvironmental stressors, providing mechanistic insights that support the development of combination therapies aimed at reversing such exhaustion.

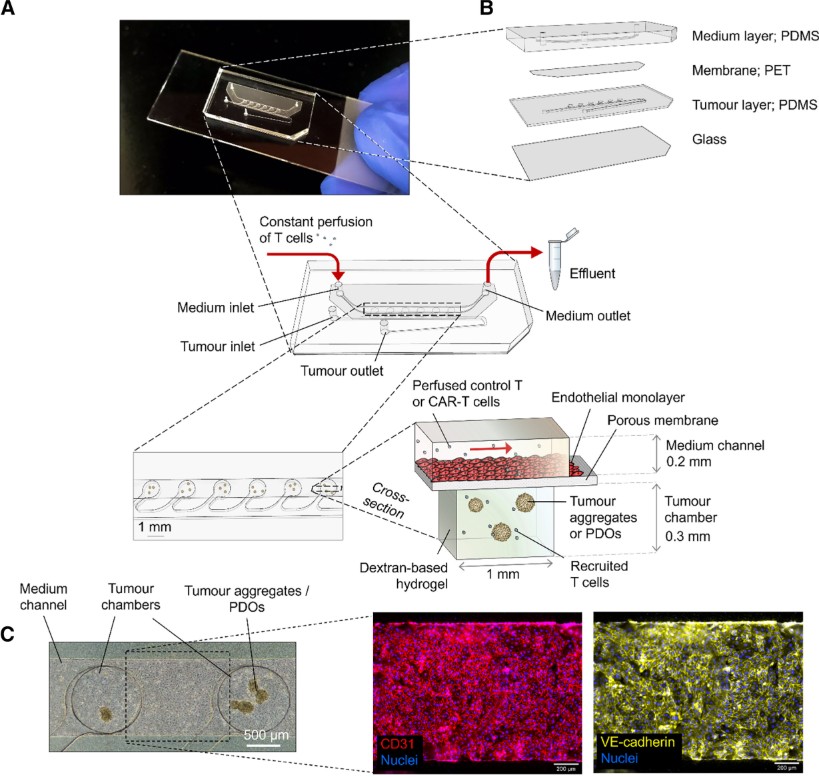

The relevance of these systems becomes even clearer in the context of cellular therapies. Maulana et al. developed a breast cancer-on-chip architecture in which patient-derived organoids or tumor aggregates were cultured directly beneath a perfused, endothelialized channel. CAR-T cells flowing through this channel underwent recruitment, extravasation, and infiltration into the tumor compartments in a manner mirroring early clinical events. Over more than a week of perfusion, the device enabled continuous measurement of cytokine release and revealed antigen-density–dependent killing as well as the effectiveness of a pharmacologic “on/off switch” to modulate CAR-T activity, features highly relevant for both therapeutic efficacy and safety evaluation(7). By capturing both the kinetics and controllability of CAR-T responses, this model highlights the value of organ-on-chip technologies in mechanistic and translational immunotherapy research.

Earlier microphysiologic tumor models help contextualize these advances. Wallstabe et al. showed that ROR1-CAR T cells could enter arterial-like flow, adhere to tumor surfaces, and penetrate multiple layers of triple-negative breast cancer tissue within a scaffold containing an intact basement membrane. Their system demonstrated that physiological shear forces and architectural complexity promote deeper CAR-T infiltration and sustained cytotoxicity, offering a bridge between traditional 3D cultures and vascularized chip models(8). These results provided much of the conceptual groundwork for the dynamic perfusion designs now used in contemporary breast cancer-on-chip devices.

Most recently, advances in vascularized tumor-on-chip technologies such as the system developed by Liu et al. have pointed toward the next generation of breast cancer modeling. Although applied to lung cancer and mesothelioma, the platform’s ability to generate fully perfusable, self-assembled human microvessels that grow into and around implanted tumor explants showcases what is technologically possible. The system supports controlled CAR-T perfusion, chemokine-modulated trafficking, and multi-omics analysis, opening the door to tumor-on-chip models that combine structural fidelity with deep molecular profiling(9). If you’d like to learn more about how these innovations represent a major leap toward truly patient-specific platforms capable of predicting efficacy and guiding clinical decisions in solid tumor immunotherapy the studies have been summarized by Vunjak-Novakovic(10)

References

- Liao CY, Engelberts P, Ioan-Facsinay A, Klip JE, Schmidt T, Ruijtenbeek R, et al. CD3-engaging bispecific antibodies trigger a paracrine regulated wave of T-cell recruitment for effective tumor killing. Commun Biol. 13 août 2024;7(1):983.

- Warwas KM, Meyer M, Gonçalves M, Moldenhauer G, Bulbuc N, Knabe S, et al. Co-Stimulatory Bispecific Antibodies Induce Enhanced T Cell Activation and Tumor Cell Killing in Breast Cancer Models. Front Immunol. 16 août 2021;12:719116.

- Cho Y, Laird MS, Bishop T, Li R, Jazwinska DE, Ruffo E, et al. CAR T cell infiltration and cytotoxic killing within the core of 3D breast cancer spheroids under the control of antigen sensing in microwell arrays. APL Bioeng. 1 sept 2024;8(3):036105.

- Röder J, Alekseeva T, Kiefer A, Kühnel I, Prüfer M, Zhang C, et al. ErbB2/HER2-targeted CAR-NK cells eliminate breast cancer cells in an organoid model that recapitulates tumor progression. Mol Ther. août 2025;33(8):3559‑75.

- Jiang X, Ren L, Tebon P, Wang C, Zhou X, Qu M, et al. Cancer‐on‐a‐Chip for Modeling Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor and Tumor Interactions. Small. févr 2021;17(7):2004282.

- Ayuso JM, Rehman S, Virumbrales-Munoz M, McMinn PH, Geiger P, Fitzgerald C, et al. Microfluidic tumor-on-a-chip model to evaluate the role of tumor environmental stress on NK cell exhaustion. Sci Adv [Internet]. 19 févr 2021 [cité 23 juill 2025];7(8). Disponible sur: https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.abc2331

- Maulana TI, Teufel C, Cipriano M, Roosz J, Lazarevski L, Van Den Hil FE, et al. Breast cancer-on-chip for patient-specific efficacy and safety testing of CAR-T cells. Cell Stem Cell. juill 2024;31(7):989-1002.e9.

- Wallstabe L, Göttlich C, Nelke LC, Kühnemundt J, Schwarz T, Nerreter T, et al. ROR1-CAR T cells are effective against lung and breast cancer in advanced microphysiologic 3D tumor models. JCI Insight. 19 sept 2019;4(18):e126345.

- Liu H, Noguera-Ortega E, Dong X, Lee WD, Chang J, Aydin SA, et al. A tumor-on-a-chip for in vitro study of CAR-T cell immunotherapy in solid tumors. Nat Biotechnol [Internet]. 17 oct 2025 [cité 28 oct 2025]; Disponible sur: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41587-025-02845-z

- Vunjak-Novakovic G. Tumor-on-chip models of CAR-T cell therapy. Nat Biotechnol [Internet]. 17 oct 2025 [cité 20 nov 2025]; Disponible sur: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41587-025-02819-1

FAQ

Traditional two-dimensional cultures are limited because they cannot replicate the mechanical pressures or chemical gradients found in human tissue. The spatial organization of the tumour microenvironment is missed in flat cultures, which leads to a failure in capturing the complexity of antigen expression. In contrast, three-dimensional systems allow the physical stroma and immune cell recruitment to be observed with high fidelity. By generating spheroids or organoids, the mechanisms of immune exclusion are dissected more effectively than in monolayers. Inter-species differences in immune physiology also limit the predictive power of murine models, necessitating human-relevant 3D platforms. These advanced microphysiological systems provide a necessary lens for understanding metastatic progression and resistance.

While therapies targeting CD19 have shown high remission rates in leukaemias, solid tumours present a fortified environment that is difficult to penetrate. Targets in blood cancers are readily accessible within the bloodstream, whereas solid malignancies require effector cells to navigate the vasculature and extravasate into tissue. This process is often obstructed by aberrant angiogenesis. Once inside, immune cells are physically excluded by the desmoplastic stroma, which acts as a mechanical barrier. Also, the metabolic environment is characterized by hypoxia and nutrient deprivation, which drives T cells towards dysfunction. Antigen-negative variants can also escape surveillance due to the mosaic nature of antigen expression in breast tumours.

These models are employed to capture the structural heterogeneity of breast tumours by developing distinct metabolic gradients. A proliferating rim and a hypoxic core are formed, which impose physical and chemical barriers similar to those found in vivo. Such architecture is required for evaluating functional capacities beyond simple cytotoxicity, such as the kinetics of immune cell trafficking. Researchers can observe whether effector cells penetrate the dense extracellular matrix or stall at the periphery. Also, the stability of the immunological synapse is assessed under metabolic stress within these systems. Patient-derived organoids facilitate personalized screenings, where specific CAR constructs are matched to a patient’s unique tumour profile to identify potential resistance mechanisms like antigen shedding.

The development of 3D spheroid culture models was the first step away from 2D monolayers. Spheroids are typically generated from established cell lines, such as MCF-7 and T-47D. They are created using simple techniques designed to prevent the cells from adhering to plastic surfaces. A common method involves culturing the cells on ultra-low attachment (ULA) plates. When forced into suspension in this manner, the cells naturally aggregate. This process causes them to self-assemble into multicellular spheroids. These models are not meant to be patient-specific but are instead used as mechanistic tools to re-introduce 3D architecture.

It was discovered by Liao et al. (2024) that efficacy in three-dimensional settings relies on specific molecular mechanics that are not visible in standard assays. Although multiple constructs appeared effective in monolayer cultures, only those binding to membrane-proximal epitopes of HER2 were found to be successful in 3D models. A necessary wave of paracrine signalling was triggered by these specific interactions, which was required for the active recruitment of T cells from the surrounding matrix. Conversely, constructs targeting distal epitopes failed to initiate this recruitment, rendering them ineffective despite high binding affinity. This research shows that the ability to trigger immune cell infiltration into the tumouroid is dependent on precise epitope selection.

Research by Cho et al. (2024) indicated that larger spheroids generate significant hypoxic cores which actively suppress the cytotoxicity of CAR T cells. The secretion of effector cytokines, such as IFNℽ and TNFɑ, was found to be reduced in these oxygen-deprived conditions. A predictive metric for therapeutic success, defined as the initial CAR T cell to spheroid area ratio, was established through this study. This quantitative framework for dosing strategies is derived from data that cannot be obtained from two-dimensional models. The physical constraints and evolved resistance mechanisms associated with tumour size are shown to impact cellular therapy outcomes.

A genetically engineered mouse-derived organoid model was employed by Röder et al. (2025) to replicate the process of Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition. This cellular state is associated with high metastatic potential and resistance to standard chemotherapy. It was revealed that while aggressive, mesenchymal-like organoids were refractory to conventional drugs, they remained highly sensitive to elimination by ErbB2-targeted CAR-NK cells. This validates the use of organoids as a rigorous testing ground for immunotherapies aimed at refractory phenotypes. The study demonstrates that even when resistance to standard treatments is present, alternative immunotherapeutic interventions can be evaluated effectively using these advanced models.

Breast cancer-on-chip systems expand analytical capabilities by introducing vascular perfusion and controlled biochemical gradients. Necessary features such as endothelial barriers and directional immune-cell trafficking are reproduced in these platforms. For example, Jiang et al. used miniaturized bioreactors to show that checkpoint inhibition restored T-cell function only in tumours with sufficient PD-L1 expression. Also, Ayuso et al. demonstrated that while NK cells initially exerted cytotoxic effects, the progressively hostile environment induced profound exhaustion. These systems enable the observation of temporal immune dysfunction driven by microenvironmental stressors, which is not possible in static spheroids or organoids alone.

In a system developed by Maulana et al., CAR-T cells flowing through an endothelialized channel were observed to undergo recruitment and extravasation into tumour compartments. This architecture allows for the continuous measurement of cytokine release and the evaluation of antigen-density-dependent killing over extended periods. Also, the effectiveness of a pharmacologic mechanism to modulate CAR-T activity was assessed. Earlier work by Wallstabe et al. demonstrated that physiological shear forces promote deeper infiltration into tissue scaffolds containing an intact basement membrane. These studies show how dynamic perfusion designs are used to capture both the kinetics and controllability of cellular responses in a realistic setting.

Advances in technology are pointing towards platforms that generate fully perfusable, self-assembled human microvessels. As demonstrated by Liu et al., these systems allow microvessels to grow into and around implanted tumour explants. Controlled perfusion of CAR-T cells and chemokine-modulated trafficking are supported by this design. Also, the integration of multi-omics analysis opens the door to models that combine structural fidelity with deep molecular profiling. These developments represent a move towards patient-specific platforms capable of guiding clinical decisions. Such studies, summarized by Vunjak-Novakovic, indicate that predicting efficacy in solid tumour immunotherapy will increasingly rely on these complex, vascularized models.