Introduction to confocal microscopy

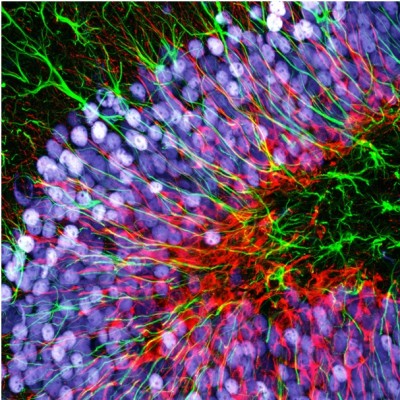

Laser scanning confocal microscopy, more generally referred as confocal microscopy, is an established microscopy technique that allows obtaining 2D or 3D high-resolution images of relatively thick samples. Confocal microscopy is a powerful technique to image fluorescent samples given its high efficiency, low background noise and the capability to optically section samples into different focal planes.

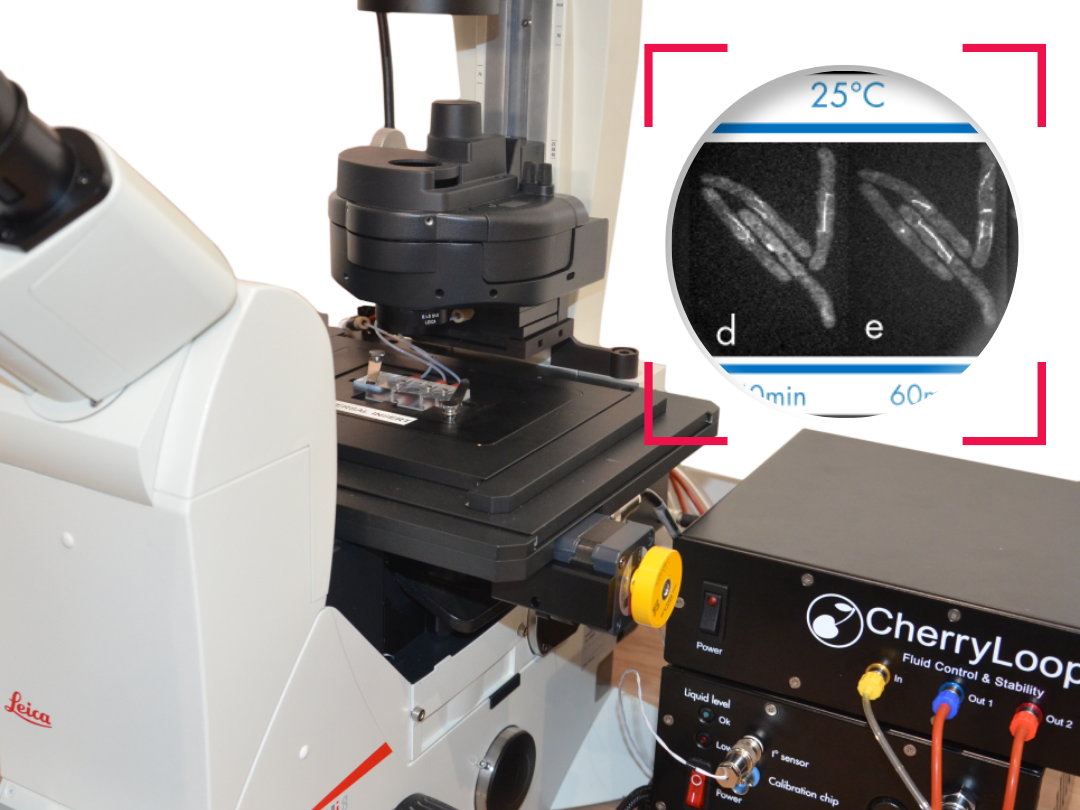

Ultra fast temperature shift device for in vitro experiments under microscopy

Laser scanning confocal microscopy “secret”?

How scanning confocal microscopy overcome limitation of wide-field fluorescence microscopy

Confocal microscopy was invented in order to mitigate and avoid problems associated with traditional wide-field microscopy. Problems of wide-field microscopy are related to:

– background noise coming from different focal planes;

– fast photo-bleaching;

– low spatial resolution due to light scattering;

– sample thickness and transparency.

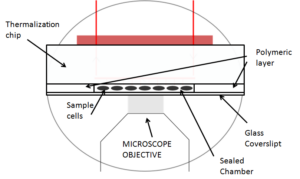

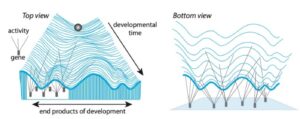

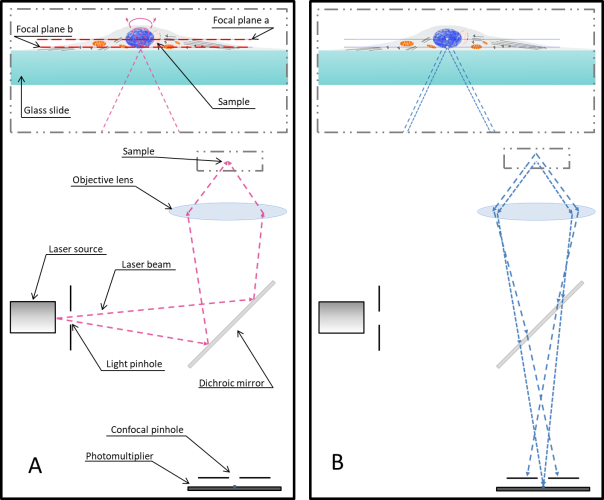

The core principle of confocal microscopy that allowed overcoming those limitations concerns the adoption of pinholes (Fig. 1) to select photons based on the focal plane they originate. In a conventional fluorescence microscope excitation light illuminates the entire area of interest at the same time (Fig. 2). All excited fluorophores then emit photons, those are collected by the objective and directed to the camera. On the other hand confocal microscopy is able to concentrate most of the excitation light in a specific spot lying on the focal plane. This small spot is optically manipulated in order to scan the sample (Fig. 2). The peak of the excited fluorophores are on the same focal plane whereas photons emitted by nearby focal planes, which generally constitute the background noise in standard fluorescence microscopy, do not contribute to the image formation being stopped by the photomultiplier pinhole. This also contributes substantially in mitigating photobleaching phenomena. The loss of fluorescence among time is much stronger in standard microscopy when compared to confocal microscopy given the fact that fluorophores are excited only during the spot illumination/acquisition.

The scanning speed is so far one of the bigger drawback of confocal microscopy. As stated above in confocal microscopy the light emitted by the laser is concentrated in a very small spot. This spot is moved at very high speed in one axis and appears by naked eyes as a line (Fig. 2B). This “line” is then moved in the other axis to slowly scan the sample. Several approaches and technologies are used to manipulate the position of the light spot; those include: galvanic mirrors, galvanic resonant mirrors, hexagonal prisms or spinning disks.

Figure 2, Sample illumination using standard fluorescence microscopy (A) and scanning animation of confocal microscopy (B). While the sample is uniformly exposed to excitation photons when imaging with a standard fluorescent microscope, confocal microscopy galvanic mirrors generate a scanning front. Laser scanning confocal microscopy has the advantage of sending most of the photon in a single focal plane spot reducing considerably fluorophores photobleaching.

This is particularly true when the second limiting factor of confocal microscopy is taken into consideration. The confocal pinhole selectivity has the drawback that it significantly decreases the light going to the sensor. Thus the sensor has to be very sensitive or the exposure time has to increase significantly. Very sensitive sensors such as photomultipliers used in laser scanning confocal microscopy can be very sensitive; on the other hand they are keen to generate false signals. Those are generally removed by repeating the scan in order to digitally remove the sensor noise but increasing again the scanning time.

In terms of resolution confocal microscopy is superior to standard fluorescence microscopy. By sectioning each single focal plane the resulting image is cleared from out of focus signals thus revealing details close to the optical diffraction limit. Moreover laser scanning confocal microscopy allows discriminating signals in the three axes thus making possible to obtain a reconstructed 3D image of the sample. Images of the scanned single focal planes can be merged directly from the confocal microscopy software of by free software such as ImageJ.

The minimum thickness of the focal plane depends on the illumination wavelength; the numerical aperture of the objective lens and of course the optical transparency of the specimen.

References

Varrone F, Mandrich L, Caputo E. Melanoma Immunotherapy and Precision Medicine in the Era of Tumor Micro-Tissue Engineering: Where Are We Now and Where Are We Going? Cancers (Basel). 2021 Nov 18;13(22):5788. doi: 10.3390/cancers13225788. PMID: 34830940; PMCID: PMC8616100.

FAQ

Laser scanning confocal microscopy is an established imaging technique. It is used to obtain two-dimensional or three-dimensional high-resolution images from samples that are relatively thick. The method is considered effective for imaging fluorescent samples. This effectiveness is due to its high efficiency and its ability to reduce background noise. A main feature of the technique is the capability to optically section samples. This allows for different focal planes to be imaged individually. These separate images can then be used to create 2D or 3D views. The resulting micrograph is cleared of signals that are out of focus.

This technique was invented to avoid problems associated with wide-field microscopy. One of these problems is background noise that comes from different, out-of-focus planes. The main principle that overcomes this limitation is the use of pinholes. These pinholes are designed to select photons based on the focal plane from which they originate. Excitation light is concentrated into a spot on a specific focal plane. Photons emitted by nearby focal planes, which would normally create background noise, are physically stopped by the photomultiplier pinhole. As a result, these out-of-focus photons do not contribute to the final image formation.

Fast photobleaching is a problem associated with traditional wide-field microscopy. In a conventional fluorescence microscope, the excitation light illuminates the entire area of interest at the same time. This continuous, broad exposure causes the loss of fluorescence over time to be much stronger. Confocal microscopy helps to lessen this effect. The method uses pinholes to concentrate the light. Fluorophores are excited only during the specific moment of spot illumination and acquisition. The sample is scanned by a small spot of light rather than being uniformly exposed. This reduces the overall time the fluorophores are excited, which in turn mitigates the photobleaching phenomenon.

One of the main drawbacks is the scanning speed. The light is concentrated in a small spot, which must be moved at high speed to scan the entire sample. This process is slower than wide-field illumination. A second limitation is related to the confocal pinhole. While the pinhole’s selectivity is good for reducing noise, it also greatly decreases the amount of light that goes to the sensor. Therefore, the sensor must be very sensitive, or the exposure time must be increased. Highly sensitive sensors, such as photomultipliers, can be prone to generating false signals, or noise. This noise is generally removed by repeating the scan, but this action further increases the total scanning time.