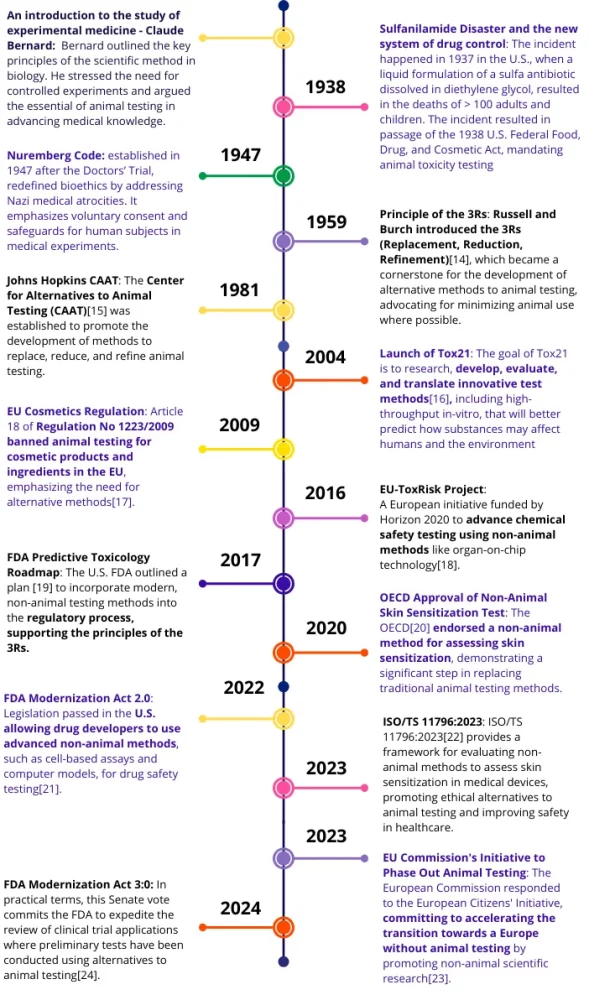

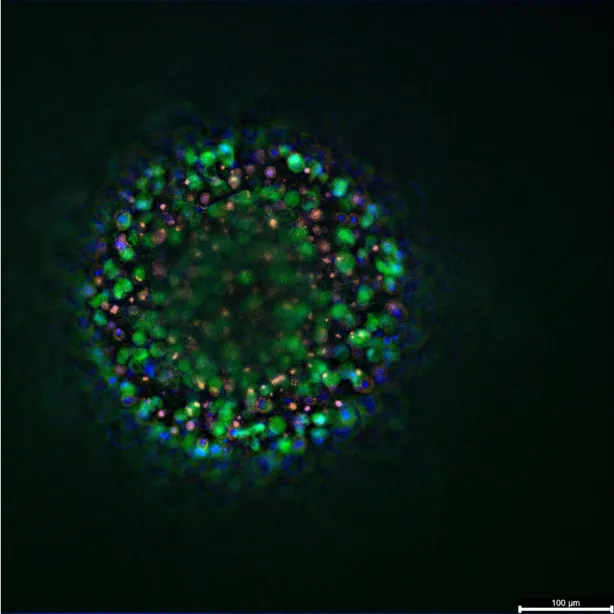

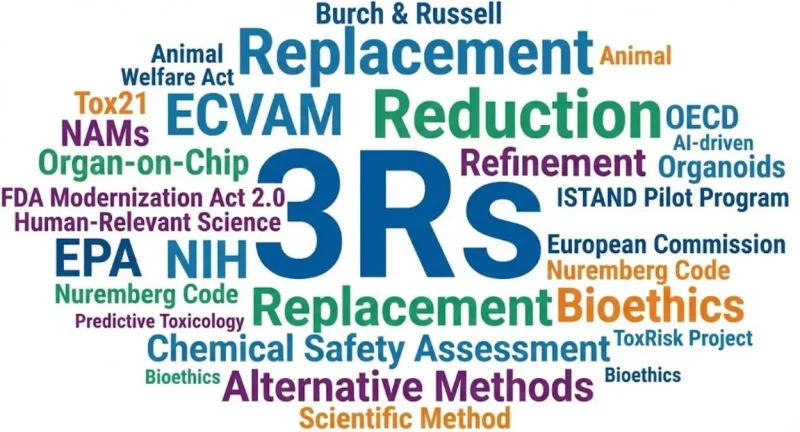

For over a century, animal experimentation has served as the bedrock of biomedical research and toxicology. From elucidating basic physiological mechanisms to ensuring the safety of life-saving drugs, animal models have been indispensable to medical progress. However, the scientific landscape is evolving. By examining the 3R timeline, we witness the rapid emergence of New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) including organ-on-chip (OoC), organoids, and AI-driven toxicology.

While the long-term vision for many is a future where animal testing is no longer necessary, the current reality is one of transition and integration. NAMs are gaining traction not merely as ethical alternatives, but as advanced scientific tools that can provide human-relevant data where animal models may fall short. Today, the challenge lies in standardizing these technologies to replace animals where possible, reduce their use in complex studies, and refine preclinical data by offering complementary human insights that animal models cannot provide alone. This report traces the journey from the establishment of animal testing as a gold standard to the modern era of hybrid testing strategies.

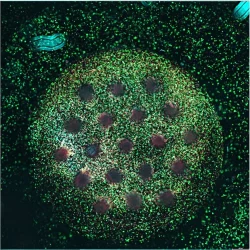

Learn more about our ready to use breast cancer organoid models.

The Foundations: Establishing standards and early regulations (Pre-2000)

To understand the current drive for alternative methods, it is essential to review how animal testing became the standard practice in the 19th and 20th centuries. The trajectory of this era moves from the establishment of the scientific method to the implementation of mandatory safety testing, and finally, to the initial development of ethical frameworks.

1865: Defining the scientific method

The scientific justification for animal research was formalized in 1865 by the French physiologist Claude Bernard. In his publication An Introduction to the Study of Experimental Medicine, Bernard outlined the principles of the scientific method in biology. He argued that medicine required controlled experiments to progress, rather than passive observation. Bernard posited that physiological mechanisms in animals were analogous to those in humans, establishing the animal model as the essential tool for advancing medical knowledge.

1938: The Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act

While Bernard provided the scientific rationale, the Sulfanilamide Disaster of 1937 precipitated the legal requirement for testing. In the United States, a liquid formulation of a sulfa antibiotic dissolved in diethylene glycol caused the deaths of over 100 people. In response, the U.S. Congress passed the 1938 Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. This legislation was a pivotal moment: it mandated that new drugs be tested for safety before marketing. Consequently, animal toxicity testing became a federal requirement, institutionalizing the practice as a primary safeguard for public health.

1947–1959: The emergence of bioethics and the 3Rs

Following World War II, the focus began to broaden to include ethical considerations. The Nuremberg Code (1947), though focused on human subjects, introduced a rigorous framework for bioethics that influenced the general conduct of research.

A specific framework for animal research emerged in 1959, when zoologist William Russell and microbiologist Rex Burch published The Principles of Humane Experimental Technique. They introduced the concept of the 3Rs: Replacement (using non-animal methods), Reduction (using fewer animals), and Refinement (minimizing suffering). This publication did not call for an end to animal testing but provided a systematic approach to minimize animal use, which remains the guiding ethical principle for the field today.

1966: The Animal Welfare Act

Public concern regarding the treatment of laboratory animals led to legislative action in the United States with the Animal Welfare Act (AWA) of 1966. This was the first federal law to regulate animals in research, setting standards for the housing, handling, and transport of specific species. However, the law explicitly excluded rats and mice bred for research, creating a regulatory distinction that persists today.

1981–1991: Institutionalizing alternatives

By the late 20th century, the development of alternatives moved from theoretical discussion to institutional implementation. In 1981, the Center for Alternatives to Animal Testing (CAAT) was founded at Johns Hopkins University. A decade later, Europe took a significant step by establishing the European Centre for the Validation of Alternative Methods (ECVAM) in 1991. ECVAM’s role was to rigorously prove that non-animal methods could provide data as reliable as traditional animal tests, a necessary step for their use in regulatory filings.

The regulatory shift and technological validation (2000–2020)

The first two decades of the 21st century marked a definitive transition. While cosmetics regulation began to phase out animal use driven largely by ethics, the scientific community simultaneously launched massive toxicology initiatives to better predict human risks.

2004: Launch of Tox21

In the United States, federal agencies (NIH, EPA, FDA) launched Toxicology in the 21st Century (Tox21). This program represented a fundamental shift in strategy: moving from observing symptoms in animals to identifying mechanisms of toxicity at the cellular level. The goal was to develop high-throughput in-vitro methods that could better predict how substances affect humans, acknowledging that animal models are not always predictive of human responses.

2004–2013: The EU cosmetic regulation

The European Union implemented a legislative phased ban that set a new global standard for the cosmetics industry, where the ethical argument for replacement was strongest.

- 2004: Testing ban on finished cosmetic products on animals.

- 2009: Ban on testing cosmetic ingredients on animals.

- 2013: Full marketing ban. This prohibited the sale in the EU of cosmetic products containing ingredients tested on animals, regardless of where the testing occurred. This forced the industry to innovate, though challenges remain for complex endpoints where animal data is still sometimes required for worker safety under other chemical regulations (like REACH).

2007–2010: Validating skin models (ECVAM and OECD)

While legislators drafted the bans, scientists faced the critical challenge of proving that non-animal methods could ensure consumer safety. The flagship example of this success is EpiSkin, a Reconstructed Human Epidermis (RHE) model industrialized by L’Oréal.

EpiSkin consists of human keratinocytes cultured on a collagen matrix at an air-liquid interface, forcing the cells to differentiate into a multi-layered tissue with a functional stratum corneum (skin barrier).

The scientific foundation was established prior to the major cosmetic bans. In 1998, ECVAM validated EpiSkin for Skin Corrosion (identifying severe chemical burns), which was subsequently adopted as OECD Test Guideline 431. This early victory proved that in vitro tissues could replicate human biological responses better than rabbits.

However, the pivotal era for cosmetics occurred between 2000 and 2010. As the EU moved toward the 2009 ban on ingredient testing, the industry needed a “full replacement” for Skin Irritation. In 2007, ECVAM formally validated EpiSkin for skin irritation, confirming it could distinguish irritants from non-irritants as a stand-alone method.

This validation led to the global adoption of OECD TG 439 in 2010. By the time the full EU marketing ban entered into force in 2013, EpiSkin had transitioned from a research novelty to a regulatory standard.

2016: EU-ToxRisk Project

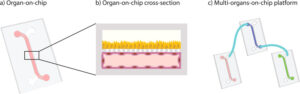

To bridge the gap between simple cell cultures and complex human biology, the EU-ToxRisk Project was launched in 2016. This initiative focused on advancing chemical safety testing using non-animal methods like organ-on-chip technology. It highlighted the potential of NAMs not just to replace animals, but to provide mechanistic data that improves risk assessment.

2017: FDA Predictive Toxicology Roadmap

The U.S. FDA published its Predictive Toxicology Roadmap in 2017. This document outlined a plan to incorporate modern, non-animal testing methods into the regulatory process. It signaled a readiness to integrate NAMs as complementary tools that could improve the predictive value of preclinical testing.

The acceleration: Pharma, legislation, and human-relevant science (Post-2020)

Since 2020, the conversation has shifted from “alternatives” to “human-relevant science.” The focus is on leveraging NAMs to address the high clinical failure rates in drug development (approx. 90%). In this era, NAMs are increasingly seen as essential for generating human-specific data that animal models cannot provide, refining the decision-making process before human trials begin.

2020: Regulatory off-ramps (OECD and FDA ISTAND)

The decade began with the FDA’s ISTAND Pilot Program (Innovative Science and Technology Approaches for New Drugs), launched in December 2020. Recognizing that technologies like microphysiological systems (MPS) did not fit traditional pathways, this created a regulatory “off-ramp” for developers to qualify novel tools. Simultaneously, the OECD endorsed a non-animal method for skin sensitization, demonstrating progress in replacing animals for specific toxicity endpoints.

2022–2023: Legislative breakthroughs

A major milestone occurred in 2022 with the FDA Modernization Act 2.0. This legislation amended the 1938 mandate, removing the requirement that all drugs must be tested on animals. It gave developers the option to use “nonclinical tests” (including cell-based assays and computer models) where appropriate. This was not a ban on animal testing, but a recognition that animal data is not the only, or always the best, way to establish safety.

In 2023, the European Commission responded to a Citizens’ Initiative by committing to accelerate the transition to non-animal science. Simultaneously, ISO/TS 11796:2023 provided a framework for evaluating medical devices using non-animal methods, further expanding the toolkit for safety assessment.

2024: End of the rabbit pyrogen test and organ-on-chip qualification

2024 marked significant technical victories. The Rabbit Pyrogen Test was replaced in the European Pharmacopoeia, a major step in reduction.

Also on September 24, 2024, the FDA accepted an industrial liver-on-chip into its ISTAND Pilot Program. This was the first organ-on-a-chip qualified for predicting drug-induced liver injury (DILI). This qualification is crucial: it does not mean the end of all animal testing, but it validates that for specific human liver toxicities, a chip can provide predictive data that is complementary (and sometimes superior) to animal models.

2025: Institutionalizing the shift

By 2025, the focus is on prioritization and funding to accelerate development:

- FDA Modernization Act 3.0: This Senate vote commits the FDA to expedite reviews of clinical trials where preliminary tests used alternatives, incentivizing the adoption of NAMs.

- NIH Prioritization: A new initiative to “Prioritize Human-Based Research Technologies” ensures that funding is no longer exclusively biased toward animal models.

- Defense Sector Shift: The U.S. Navy announced the end of biomedical research testing on cats and dogs, citing the availability of advanced human-based platforms.

- UK Phase Out: The UK government unveiled plans to phase out animal testing, aiming to accelerate the uptake of alternatives.

Global harmonization

- China: The November 2025 NMPA reforms signal a move toward accepting NAMs for cosmetics.

- Brazil: A July 2025 ban solidifies the country’s move away from animal testing for cosmetics.

- South Korea: Continues to validate methods through KoCVAM to support its industry.

Future outlook: 2026 and beyond

Looking ahead to 2026, the European Commission is set to publish a “Roadmap Towards Phasing Out Animal Testing for Chemical Safety Assessments”. Announced in 2023 after a European Citizens’ Initiative (ECI) “Save cruelty-free cosmetics – Commit to a Europe without animal testing”, as a guiding plate to replace and refine animal testing in chemical safety.

Conclusion: As we move forward, the role of NAMs is becoming increasingly central. While animal models remain necessary for studying complex systemic interactions that current technology cannot yet fully replicate, the rise of organ-chips and AI offers a powerful path forward. These technologies allow researchers to refine their understanding with human-specific data, reduce the number of animals needed by screening out toxic candidates early, and gradually replace animal testing in specific contexts. The goal remains a future where scientific excellence and ethical stewardship are fully aligned.

FAQ

In 1865, the scientific basis for using animals was formalised by Claude Bernard. In An Introduction to the Study of Experimental Medicine, the rules of the scientific method were outlined. It was argued that controlled tests were needed for medicine to advance, rather than just observation. Physiological processes in animals were viewed as similar to humans. The animal model was then established as a main tool. Later, the Sulfanilamide Disaster of 1937 caused over 100 deaths due to a toxic antibiotic mixture. This tragedy led to the 1938 Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act in the US. Safety testing for new drugs was made mandatory by this law. This made animal toxicity testing a federal requirement and a main safeguard for public health.

The concept of the 3Rs was introduced in 1959 by William Russell and Rex Burch. In their text, The Principles of Humane Experimental Technique, a systematic method for research was presented. Replacement refers to the use of non-animal methods. Reduction involves the use of fewer animals in studies. Refinement is defined as minimising suffering. An end to animal testing was not called for by this publication. Instead, a framework was provided to lower animal use. These standards remain the guiding ethical principles for the field today. Bioethics had also been influenced earlier by the Nuremberg Code of 1947. Although that code focused on humans, a rigorous structure for research conduct was established.

A legislative phased ban was implemented by the European Union between 2004 and 2013. Testing on finished cosmetic products was banned in 2004. Subsequently, a ban on testing cosmetic ingredients was introduced in 2009. The full marketing ban came into force in 2013. The sale of cosmetics with ingredients tested on animals was prohibited by this rule, regardless of where the testing took place. This forced innovation within the industry. Yet, difficulties persist for complex endpoints. Animal data is still sometimes needed for worker safety under other chemical regulations, such as REACH. This legislation set a new global standard for the industry where ethical arguments were strongest.

New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) are being viewed as advanced scientific tools. These methods include organ-on-chip (OoC), organoids, and toxicology using AI. Data relevant to humans can be provided by NAMs where animal models may fail. The current scientific environment is described as one of transition. While a future without animal testing is envisioned by many, animals are still used today. Technologies are being standardised to replace animals where possible. Animal use is also reduced in complex studies through these methods. Preclinical data is refined by offering human insights that are not provided by animal models alone. The aim is to address high clinical failure rates in drug development.

Toxicology in the 21st Century (Tox21) was launched in 2004 by US federal agencies, including the NIH, EPA, and FDA. A major shift in strategy was represented by this programme. The focus moved from observing symptoms in animals to identifying toxicity mechanisms at the cellular level. High-throughput in-vitro methods were developed to better predict how substances affect humans. It was acknowledged that animal models do not always predict human responses accurately. Later, the EU-ToxRisk Project was launched in 2016 to bridge gaps between simple cell cultures and complex human biology. This initiative focused on chemical safety testing using non-animal methods like organ-on-chip technology. Mechanistic data is provided by these tools to improve risk assessment.

On September 24, 2024, the Emulate Liver-Chip S1 was accepted by the FDA into its ISTAND Pilot Program. This was the first organ-on-a-chip to be qualified for predicting drug-induced liver injury. This qualification validates that a chip can provide predictive data for specific human liver toxicities. In some cases, this data is considered complementary or superior to animal models. This achievement does not signify the immediate end of all animal testing. Yet, it marks a technical victory in the move towards human-relevant science. Also, the Rabbit Pyrogen Test was replaced in the European Pharmacopoeia in 2024, contributing to reduction efforts. These events demonstrate that non-animal methods are gaining acceptance for specific regulatory endpoints.

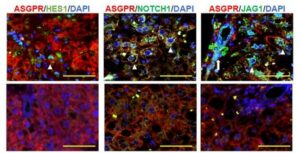

A genetically engineered mouse-derived organoid model was employed by Röder et al. (2025) to replicate the process of Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition. This cellular state is associated with high metastatic potential and resistance to standard chemotherapy. It was revealed that while aggressive, mesenchymal-like organoids were refractory to conventional drugs, they remained highly sensitive to elimination by ErbB2-targeted CAR-NK cells. This validates the use of organoids as a rigorous testing ground for immunotherapies aimed at refractory phenotypes. The study demonstrates that even when resistance to standard treatments is present, alternative immunotherapeutic interventions can be evaluated effectively using these advanced models.

Reliable alternatives are required for regulatory bans to function effectively. Between 2007 and 2010, the scientific validity of the EpiSkin method was endorsed by ECVAM. This method uses a reconstructed human epidermis model. Test Guideline 439 was adopted by the OECD, allowing companies to test for skin irritation using human tissue models. It was proven that NAMs could fully replace animal tests for specific, defined endpoints. Earlier, the European Centre for the Validation of Alternative Methods (ECVAM) had been established in 1991. Its role was to prove that non-animal methods could provide data as reliable as traditional animal tests. This validation is a necessary step for these methods to be used in regulatory filings.

By 2025, the focus is expected to shift towards prioritisation and funding to accelerate development. The FDA Modernization Act 3.0 commits the FDA to expedite reviews of clinical trials where preliminary tests used alternatives. A new initiative by the NIH ensures that funding is not exclusively biased towards animal models. In the defence sector, the end of biomedical research testing on cats and dogs was announced by the US Navy. Globally, reforms in China signal a move towards accepting NAMs for cosmetics. A ban on animal testing for cosmetics is solidified by Brazil. Plans to phase out animal testing were also unveiled by the UK government. These actions incentivise the adoption of non-animal methods.

Looking ahead to 2026, a plan towards phasing out animal testing for chemical safety assessments is set to be published by the European Commission. This announcement followed a European Citizens’ Initiative titled “Save cruelty-free cosmetics”. This document acts as a guide to replace and refine animal testing in chemical safety. The role of NAMs is becoming increasingly central as we move forward. Yet, animal models remain necessary for studying complicated interactions within the whole body that current technology cannot yet fully replicate. The number of animals needed is reduced by screening out toxic candidates early with organ-chips and AI. Researchers are allowed to refine their understanding with data specific to humans. The ultimate goal is a future where scientific excellence is aligned with ethical stewardship.