Modern drug discovery is shifting from “one-size-fits-all” animal models toward new-approach methodologies (NAMs) that capture human-specific biology early in the pipeline. At a time when obesity, type 2 diabetes and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis are rising worldwide, where rodent adipose tissue differs markedly from its human counterpart(1), such human-relevant systems promise sharper insights into disease pathways and therapeutic responses. Two complementary NAMs, in vitro adipose tissue models (organoids and organ-on-chip systems), are transforming how researchers interrogate endocrine function, immune interactions and drug responses in fat. Together, these 3D micro-tissues and microfluidic platforms promise faster, more ethical and, above all, more predictive preclinical testing.

Why Preclinical Testing Needs Human-Relevant In Vitro Adipose Tissue Models

Preclinical testing acts as the safety and efficacy checkpoint between basic discovery and first-in-human trials. Investigators must confirm target engagement, pharmacokinetics and potential toxicities before dosing volunteers. Historically, this meant rodent studies, supplemented in some cases by larger mammals. Yet species-specific differences run deep: mice harbor proportionally more thermogenic brown/beige fat and respond quite differently to β-adrenergic stimulation than humans(2). Such gaps help explain why metabolic drug candidates show one of the highest attrition rates when advancing from animals to clinic.

In vitro adipose tissue models aim at closing this translational gap.

- Organoids supply self-organized 3D depots that secrete adipokines, store and mobilize lipids, and recruit resident immune cells; capabilities that 2D adipocyte monolayers and most rodent models lack.

- Organ-on-chip platforms embed adipocytes (and often endothelial or immune co-cultures) within perfused micro-channels, emulating mechanical cues and nutrient flux that shape real-world fat physiology.

By integrating these systems alongside traditional animal studies, researchers can flag failures earlier, refine dose estimates and satisfy emerging regulatory pathways. The U.S. FDA’s 2025 roadmap, for example, maps a stepwise reduction (though not yet elimination) of mandatory animal tests as robust NAM validation data accumulate(3). As the field converges on standardized culture protocols and quality-control metrics, these models are poised to make preclinical evaluation both more predictive and more humane.

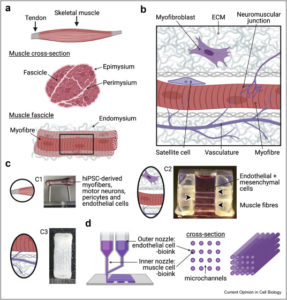

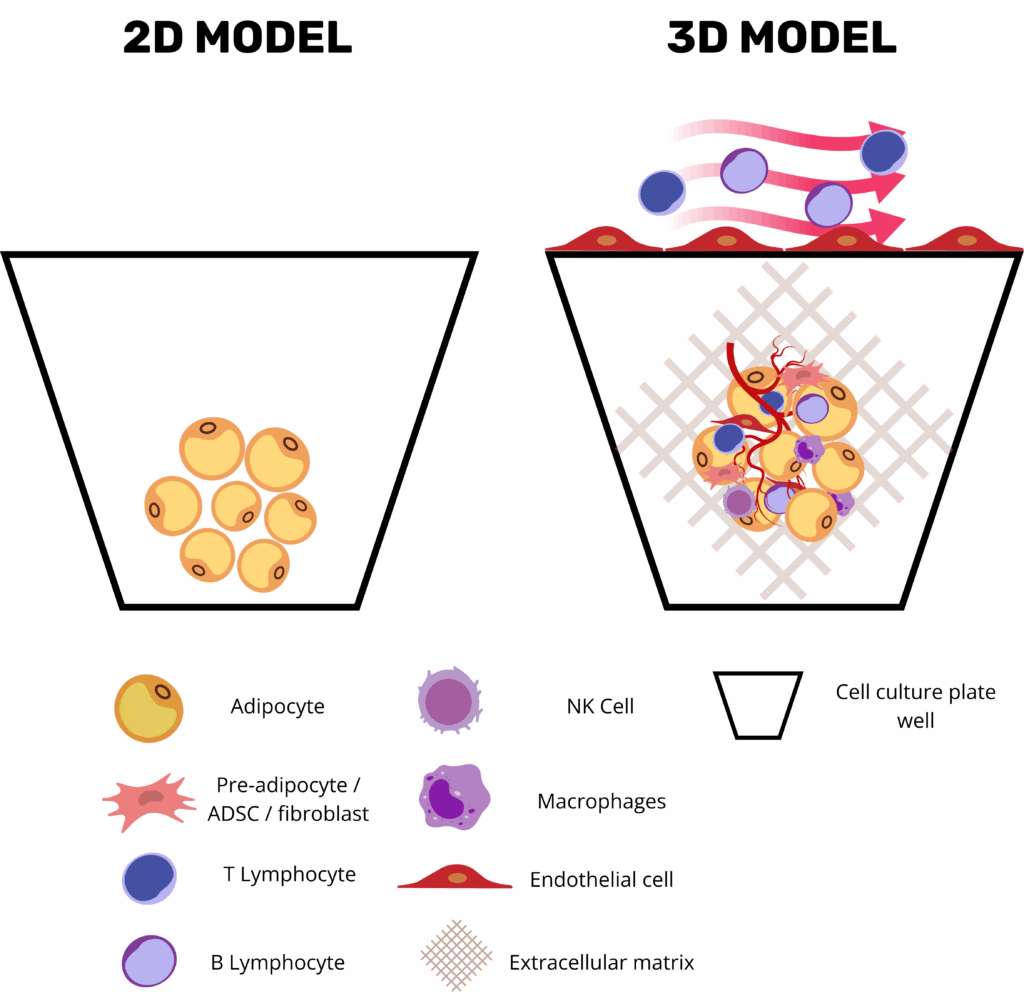

Strategic Advantages of Adipose Tissue Organoids and On-Chip Platforms

Three-dimensional adipose tissue organoids and microphysiological adipose tissue on chip platforms have become central tools in metabolic-disease research by combining the human relevance of primary adipose tissue with the precision, modularity, and automation of modern bioengineering. Unlike conventional 2D adipocyte monolayers, organoids retain the stromal–vascular complexity of native white or brown fat, where mature lipid-laden adipocytes coexist with endothelial cells, progenitor populations, and resident immune cells in an ECM-rich niche. This enables the preservation of key endocrine programs such as leptin and adiponectin secretion, as well as depot-specific transcriptional signatures.

Critically, these platforms offer high experimental versatility: researchers can fine-tune the microenvironment by including or omitting vascular perfusion, endothelial or immune cells, and by selecting scaffolds that mimic specific extracellular matrix properties. Microfluidic fat-on-chip systems further enhance physiological relevance by introducing programmable nutrients and hormone cycles under dynamic flow, simulating shear stress, nutrient delivery, waste removal, and even immune cell trafficking across vascular compartments(4).

Beyond their biological sophistication, these models are engineered for analytical accessibility and scalability. Culture systems are often compatible with imaging techniques and real-time biosensors and designed to support both low- and high-throughput workflows. This accessibility synergizes powerfully with new-generation imaging, in silico modeling, and machine learning approaches, enabling quantitative readouts of complex phenomena such as insulin-stimulated glucose uptake, β-adrenergic lipolysis, and secretion of inflammatory chemokines. Importantly, such platforms allow for parallel evaluation of target-specific efficacy and off-target toxicity in a controlled, human-relevant microenvironment.

Current Applications of In Vitro Adipose Tissue Models in Pre-clinical Testing

Adipose-tissue organoids have evolved into a versatile pre-clinical platform that now underpins much of modern metabolic-disease research. By finely tuning the culture environment, investigators can reproduce every major facet of “unhealthy” fat: lipid-droplet hypertrophy, heightened basal lipolysis, a shift in the adiponectin-to-leptin ratio, insulin-signaling defects, and the low-grade inflammatory milieu typical of metabolically diseased adipose tissue(4). Adding pro-inflammatory cytokines or live macrophages deepens that phenotype, generating a chronic, depot-specific inflammation that is ideally suited for evaluating small-molecule or antibody therapies. Because white-adipose organoids (WAOs) can be formed in miniaturized arrays, entire chemical libraries are now screened in parallel; automated imaging and secretome read-outs swiftly flag compounds that normalize lipid storage, temper cytokine release, or restore glucose uptake.

The same three-dimensional scaffolds support co-cultures designed to model insulin resistance. Embedding pre-adipocytes with activated macrophages yields a stable drop in GLUT4 translocation and AKT phosphorylation, giving researchers a human-relevant testbed for PPARγ modulators and next-generation insulin sensitizers(5).

Importantly, when these adipose organoids are grown within biomaterials that mimic the extracellular matrix, such as hydrogels, they also offer a unique opportunity to study how mechanical cues affect fat cell behavior. In this setting, adipocytes respond to stiffness, tension, and pressure by activating mechanotransduction pathways that influence their growth, metabolism, and inflammatory state. These responses reflect how real adipose tissue remodels under stress, such as during obesity or fibrosis, and open the door to testing how mechanical interventions or ECM-targeting drugs could modulate adipose function in disease(6).

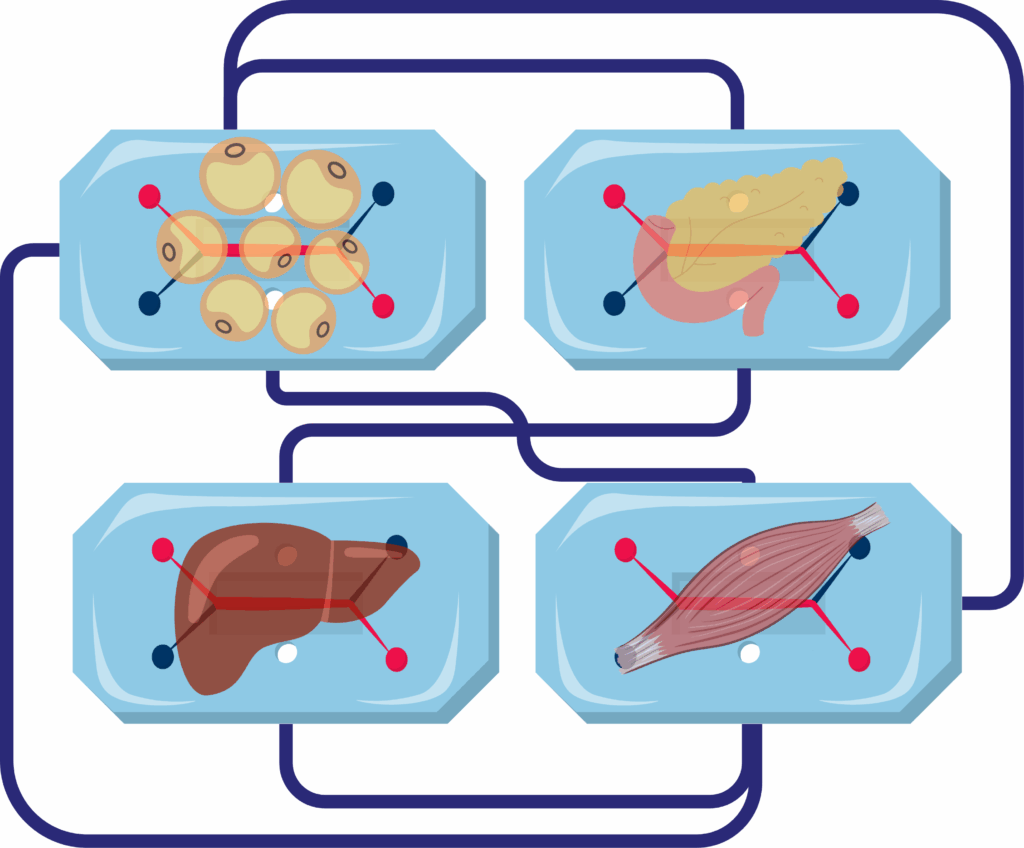

Coupling adipose tissue organoids with liver, muscle, or pancreatic modules on microfluidic platforms enables the study of inter-organ crosstalk in metabolic disease. These integrated systems offer insight into how restoring healthy adipose function influences distal tissues, reveal off-target drug effects, and better predict human responses than isolated cell models. For example, in the adipose–liver chip developed by Slaughter et al., hepatocyte steatosis and insulin resistance emerged only in the presence of dysfunctional adipose tissue, and metformin failed to reduce lipid accumulation at clinically relevant doses, highlighting the critical role of adipose-derived signals in NAFLD progression and drug response(7).

Regenerative applications are emerging just as rapidly. Brown- and beige-adipose organoids cultured ex vivo can be implanted beneath the skin or kidney capsule of rodent models; once vascularized, they raise whole-body energy expenditure, blunt weight gain, lower fasting glucose, and, in dyslipidemic animals, bring serum cholesterol and triglycerides within a healthy range. Beyond metabolic regulation, recent work demonstrates that engineered adipose tissue organoids may serve as direct therapeutic agents in cancer, as illustrated by adipose manipulation transplantation (AMT). In this approach, CRISPRa-modified adipose organoids,programmed to upregulate thermogenic and metabolic genes such as UCP1, outcompete tumors for glucose and fatty acids, thereby suppressing tumor growth and progression in both xenograft and genetically engineered cancer models. These findings establish adipose organoids not only as tools for metabolic restoration but also as customizable, cell-based therapeutic platforms for preclinical testing and intervention in cancer(8).

Finally, fat-on-chip platforms are proving useful beyond classical metabolism. Vascularized “omentum” chips that pair adipocytes with mesothelial and endothelial layers allow cancer biologists to dissect how tumor cells exploit adipose niches, while toxicologists use the same devices to gauge how long lipophilic drugs or environmental chemicals persist in human fat and whether they perturb systemic lipid handling. Taken together, these advances show that three-dimensional adipose systems are no longer experimental curiosities; they are already reshaping drug discovery, disease modelling, and early-stage regenerative medicine.

Challenges and Limitations of In Vitro Adipose Tissue Models

Despite their promising applications, adipose tissue organoids face several challenges and limitations that must be addressed to fully realize their potential in preclinical testing.

Complexity of Generation and Maintenance: Creating and sustaining functional adipose tissue organoids require specialized techniques, expertise, and resources. The process involves precise control over the cellular microenvironment to promote proper differentiation and maturation of adipose cells. This complexity can limit the widespread adoption of organoids in research settings, particularly for laboratories with limited access to advanced technologies and training.

Variability and Reproducibility: Organoids derived from different patients or under varying conditions can exhibit differences in structure and function, impacting the reproducibility and reliability of research findings. Standardizing protocols for organoid generation and culture is essential to ensure consistent and comparable results across studies. Additionally, improving the scalability of organoid production is necessary to facilitate large-scale research and drug screening efforts.

Limitations in Replicating Human Physiology: While adipose tissue organoids provide a more accurate representation of adipose tissue than traditional models, they may not fully capture the complexity of systemic interactions and long-term disease progression. Integrating organoids with other tissue models and advanced technologies, such as microfluidic systems and organ-on-a-chip platforms, can help overcome these limitations and enhance the predictive power of organoid-based research(9)

Future Directions of In vitro Adipose Tissue Models Research

The future of adipose tissue organoid research holds exciting possibilities for advancing our understanding of metabolic diseases and improving therapeutic interventions.

Integration with Advanced Technologies: One promising direction is the integration of organoids with advanced technologies, such as gene editing and high-throughput screening. By leveraging CRISPR/Cas9 and other gene-editing tools, researchers can manipulate specific genes within organoids to study their roles in adipose tissue function and disease. This approach can provide valuable insights into genetic factors influencing obesity, diabetes, and other metabolic disorders, paving the way for targeted therapies.

Development of Multi-Tissue Models: Another area of potential advancement is the development of more sophisticated organoid models that incorporate additional cell types and tissue interactions. For example, creating multi-tissue organoids that include adipose tissue, liver, and muscle cells can provide a more comprehensive understanding of metabolic processes and their systemic effects. These complex models can help elucidate the intricate relationships between different tissues and identify new therapeutic targets for metabolic diseases.

Enhancing Scalability and Reproducibility: Enhancing the scalability and reproducibility of organoid production is also a crucial focus for future research. Developing standardized protocols and automated systems for generating and maintaining organoids can facilitate large-scale studies and drug screening efforts. Additionally, improving the consistency and quality of organoids derived from different patients will enhance the reliability of personalized medicine approaches, enabling more accurate predictions of therapeutic responses and disease outcomes.

Resources

- Liu X, Yang J, Yan Y, Li Q, Huang RL. Unleashing the potential of adipose organoids: A revolutionary approach to combat obesity-related metabolic diseases. Theranostics. 2024;14(5):2075‑98. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10945346/

- Börgeson E, Boucher J, Hagberg CE. Of mice and men: Pinpointing species differences in adipose tissue biology. Front Cell Dev Biol. 15 sept 2022;10:1003118. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36187476/

- U.S. Food & Drug Admnistration. Roadmap to Reducing Animal Testing in Preclinical Safety Studies [Internet]. 2025. Disponible sur: https://www.fda.gov/media/186092/download?attachment

- Contessi Negrini N, Pellegrinelli V, Salem V, Celiz A, Vidal-Puig A. Breaking barriers in obesity research: 3D models of dysfunctional adipose tissue. Trends Biotechnol. mai 2025;43(5):1079‑93. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/39443224/

- Lumeng CN, Deyoung SM, Saltiel AR. Macrophages block insulin action in adipocytes by altering expression of signaling and glucose transport proteins. Am J Physiol-Endocrinol Metab. janv 2007;292(1):E166‑74. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16926380/

- Sakers A, De Siqueira MK, Seale P, Villanueva CJ. Adipose-tissue plasticity in health and disease. Cell. févr 2022;185(3):419‑46. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35120662/

- Slaughter VL, Rumsey JW, Boone R, Malik D, Cai Y, Sriram NN, et al. Validation of an adipose-liver human-on-a-chip model of NAFLD for preclinical therapeutic efficacy evaluation. Sci Rep. 23 juin 2021;11(1):13159. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34162924/

- Nguyen HP, An K, Ito Y, Kharbikar BN, Sheng R, Paredes B, et al. Implantation of engineered adipocytes suppresses tumor progression in cancer models. Nat Biotechnol [Internet]. 4 févr 2025 [cité 4 avr 2025]; Disponible sur: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41587-024-02551-2

- McCarthy M, Brown T, Alarcon A, Williams C, Wu X, Abbott RD, et al. Fat-On-A-Chip Models for Research and Discovery in Obesity and Its Metabolic Comorbidities. Tissue Eng Part B Rev. 1 déc 2020;26(6):586‑95. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32216545/

FAQ

Preclinical testing is used to confirm target engagement, pharmacokinetics, and potential toxicities before human trials. Rodent studies have historically been used for this purpose. There are, however, differences between rodent and human adipose tissue. These include differences in the amount of thermogenic fat and in responses to certain stimuli. Such gaps may help to explain why metabolic drug candidates have a high rate of attrition when advancing from animal tests to clinical studies. In vitro adipose tissue models, such as organoids and organ-on-chip systems, are intended to close this translational gap. By using these human-relevant systems, researchers may be able to flag failures earlier and refine dose estimates.

Adipose tissue organoids are self-organised, three-dimensional depots of fat cells grown in a laboratory. They are a type of in vitro adipose tissue model. These structures are able to secrete adipokines, which are hormones released by fat. They can also store and mobilize lipids. In some models, resident immune cells can be recruited. These are capabilities that two-dimensional (2D) adipocyte monolayers often lack. Organoids retain the stromal–vascular complexity found in native fat. This means mature, lipid-laden adipocytes coexist with endothelial cells, progenitor populations, and resident immune cells in a niche rich with extracellular matrix. This composition allows for the preservation of key endocrine programs.

Organ-on-chip platforms are a type of microphysiological system. For adipose tissue, these platforms embed adipocytes within micro-channels that are continuously perfused with fluid. Often, co-cultures are included. These may contain endothelial or immune cells. The systems are designed to emulate the mechanical cues and nutrient flux that shape fat physiology in the body. Microfluidic fat-on-chip systems can introduce programmable cycles of nutrients and hormones under dynamic flow. This setup simulates shear stress, the delivery of nutrients, and the removal of waste. It also allows for modelling the trafficking of immune cells across vascular compartments.

These three-dimensional platforms provide high experimental versatility. Researchers are able to fine-tune the microenvironment. This includes the ability to add or omit vascular perfusion. Endothelial or immune cells can also be included or left out. Scaffolds can be selected that copy the specific properties of the extracellular matrix. This allows for the preservation of depot-specific transcriptional signatures. The models are also engineered for analytical accessibility. They are often compatible with imaging techniques and real-time biosensors. This design supports both low- and high-throughput workflows. This versatility allows for quantitative readouts of complex biological phenomena.

The culture environment for adipose-tissue organoids can be finely tuned. This control permits investigators to reproduce the main facets of "unhealthy" fat. These features include lipid-droplet hypertrophy, which is the enlargement of fat cells. Heightened basal lipolysis and a shift in the adiponectin-to-leptin ratio can also be modelled. Insulin-signaling defects are reproduced. The low-grade inflammatory milieu typical of metabolically diseased adipose tissue is also present. Pro-inflammatory cytokines or live macrophages can be added to the culture. This deepens the unhealthy phenotype. A chronic, depot-specific inflammation is generated. This system is suited for evaluating small-molecule or antibody therapies.

Yes, three-dimensional scaffolds are used to support co-cultures that are designed to model insulin resistance. In one example, pre-adipocytes are embedded with activated macrophages. This co-culture is reported to yield a stable drop in GLUT4 translocation and AKT phosphorylation. This provides researchers with a human-relevant testbed. This testbed can be used to study PPARγ modulators. It is also suitable for testing next-generation insulin sensitizers. The platforms are engineered to allow quantitative readouts of complex phenomena, such as measuring insulin-stimulated glucose uptake.

Adipose organoids can be grown within biomaterials, such as hydrogels. These materials are chosen to copy the extracellular matrix. This setup gives researchers an opportunity. They can study how mechanical cues affect the behaviour of fat cells. In this setting, adipocytes respond to stiffness, tension, and pressure. These forces activate mechanotransduction pathways. These pathways are known to influence the growth, metabolism, and inflammatory state of the cells. These responses show how real adipose tissue remodels under stress, which occurs during conditions like obesity or fibrosis. This allows for testing how mechanical interventions or drugs targeting the matrix could modulate adipose function.

Adipose tissue organoids can be coupled with other tissue modules on microfluidic platforms. These other modules may include liver, muscle, or pancreatic models. This integrated setup permits the study of inter-organ crosstalk in metabolic disease. These systems provide information on how restoring healthy adipose function can influence distal tissues. They can also reveal off-target drug effects. In an adipose–liver chip, hepatocyte steatosis and insulin resistance were seen to emerge. This occurred only when dysfunctional adipose tissue was present in the system. This finding showed the part that adipose-derived signals play in NAFLD progression.

Yes, regenerative applications are being developed. Brown- and beige-adipose organoids can be cultured ex vivo. They are then implanted into rodent models. After vascularization, these implants are shown to raise whole-body energy expenditure and blunt weight gain. Fasting glucose is also lowered. Engineered adipose tissue organoids may also serve as therapeutic agents in cancer. In one strategy, CRISPRa-modified adipose organoids were programmed to upregulate thermogenic genes like UCP1. These organoids were found to outcompete tumours for glucose and fatty acids. This action suppressed tumour growth in cancer models.

Several challenges must be addressed. Creating and sustaining functional adipose tissue organoids requires specialized techniques and resources. The process involves precise control over the cellular microenvironment. This complexity can limit widespread adoption. Variability and reproducibility are also concerns. Organoids derived from different patients or under varying conditions can show differences in structure and function. Standardizing protocols for organoid generation is needed to ensure consistent results. Improving the scalability of organoid production is also necessary for large-scale research. While more accurate than traditional models, organoids may not fully capture systemic interactions or long-term disease progression.