Luminal A and B breast cancers, collectively known as hormone receptor–positive (HR+) disease, represent the most common subtype of breast cancer and remain a major focus of translational research and drug development. Traditionally, studies of luminal tumors have relied on 2D cell lines and animal models, which helped establish endocrine therapies but often fail to predict clinical response. The emergence of luminal breast cancer organoid models, along with advanced spheroid cultures and tumor-on-a-chip systems, has transformed the landscape by providing physiologically relevant platforms that better capture tumor heterogeneity, hormone signaling, microenvironmental cues, and patient-specific drug sensitivities. These next-generation approaches bridge the gap between conventional in vitro assays and clinical outcomes, supporting precision medicine efforts for HR+ disease. By enabling high-fidelity modeling of endocrine therapy response, resistance mechanisms, and tumor–stroma or tumor–immune interactions, these tools are helping to accelerate preclinical discovery and improve therapeutic decision-making for luminal breast cancer.

Learn more about our ready to use breast cancer organoid models.

The clinical and biological challenge of luminal A/B cancer

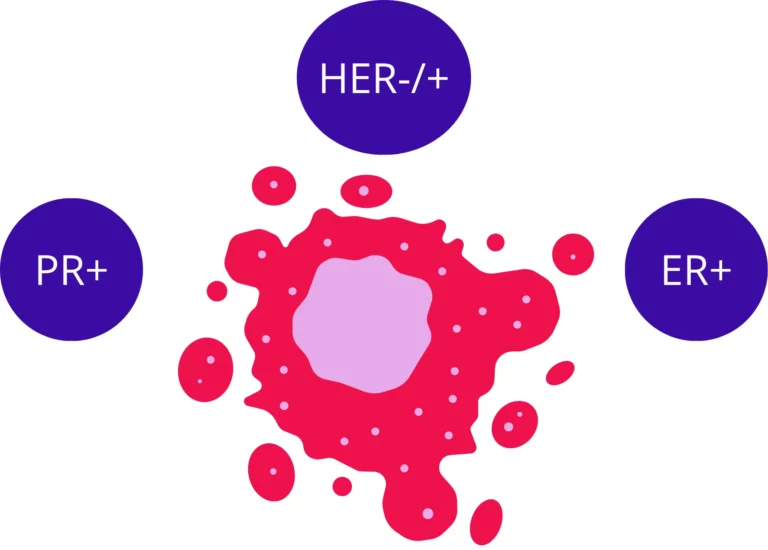

Breast cancer is not a single disease but a complex and heterogeneous collection of related malignancies. Gene expression profiling has reproducibly identified four main molecular subtypes: Luminal A, Luminal B, HER2-enriched, and Basal-like (or Triple-Negative, TNBC). The Luminal subtypes, defined by their expression of hormone receptors (HR+) (namely the estrogen receptor (ɑ, or ER) and progesterone receptor (PR)) are the most prevalent, accounting for 70-80% of all breast cancer cases(1).

- Luminal A (ER+/PR+/HER2-, Ki-67 low): This is the most common subtype (50-60% of cases). It is characterized by low levels of the proliferation marker Ki-67, resulting in a slower-growing, lower-grade tumor with a generally good prognosis and high responsiveness to endocrine therapy.

- Luminal B (ER+/PR+/HER2-/+ and Ki-67 high): This subtype is more aggressive, defined by a higher proliferation rate (high Ki-67) and, in some cases, HER2-overexpression. It carries a worse prognosis than Luminal A.

While initial treatment for HR+ breast cancer, centered on endocrine therapies (e.g., tamoxifen, aromatase inhibitors) that target its estrogen dependency, is highly effective, two central clinical challenges remain. The first is Acquired Endocrine Resistance (AER), wherein tumors that initially respond to hormone blockade eventually recur, often driven by complex bypass signaling pathways or TME-driven phenotypes. The second is late-stage metastatic recurrence where patients can relapse at distant sites years after completing adjuvant therapy and being declared disease-free.

These two phenomena (AER and late, organ-specific metastasis) are the primary drivers of mortality in Luminal A/B breast cancer. Consequently, preclinical models for this subtype must be judged by their ability to faithfully recapitulate these specific biological processes. By this standard, traditional research models have been demonstrably inadequate.

Notably, 2D cell lines (MCF-7, T-47D) lack 3D physiological context, genetic heterogeneity, and fail to model endocrine resistance. In vivo models also struggle(2). Genetically engineered mouse Models (GEMMs) often develop ER-negative tumors, making them poor surrogates(3).

On the other hand, patient-derived xenografts (PDX) preserve tumor genomics but are slow, costly, and biased toward aggressive cancers. Critically, PDX models replace the human tumor microenvironment (TME) with murine components and fail to replicate the disease’s signature bone metastasis, instead defaulting to the lungs. This creates a “modeling gap” for studying the key questions of resistance and metastatic spread.

From Monolayers to Spheroids: Re-establishing 3D Architecture

The first evolutionary step away from the 2D monolayer was the development of 3D spheroid culture models. These models are not intended to be patient-specific, but rather serve as mechanistic tools to re-introduce the fundamental biological component of 3D architecture, which is missing from dish culture.

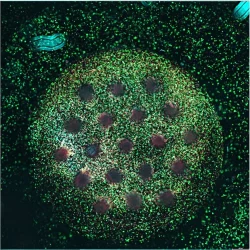

3D spheroids are typically generated from established cell lines, such as the Luminal A workhorses MCF-7 and T-47D. This is achieved using simple techniques that prevent cell adhesion to plastic, such as the hanging drop method or, more commonly, culturing cells on ultra-low attachment (ULA) plates. Forced into suspension, the cells aggregate and self-assemble into multicellular spheroids(4).

The importance of this 3D aggregation is not merely physical; it is a profound biological shift. This architecture re-establishes critical cell-cell and cell-ECM interactions, which in turn triggers a cascade of phenotypic changes more representative of an in vivo tumor nodule. These include:

- Physiological Gradients: Spheroids larger than a few hundred micrometers develop in vivo-like gradients of oxygen, nutrients, and waste products, leading to a hypoxic, necrotic core surrounded by a proliferative rim.

- Altered Gene Expression: This 3D context alters gene expression, leading to slower proliferation (a higher fraction of G0-dormant cells) and reduced apoptotic potential compared to 2D.

- Altered Metabolism: 3D culture has been shown to substantially increase the activity of drug-metabolizing enzymes, such as CYP3A4, and alter the expression of drug transporters.

The primary utility of the spheroid model is to study mechanisms of drug resistance that are dependent on 3D architecture and cell-cell interactions.

Chemotherapy Resistance: It is a well-established finding that 3D spheroids are inherently more resistant to chemotherapy than their 2D counterparts. Studies using Luminal (MCF-7, T-47D, BT-474) and TNBC cell lines show that spheroids demonstrate significantly higher resistance to standard chemotherapeutics like paclitaxel, doxorubicin, docetaxel, and arsenic. This resistance is attributed to a combination of factors, including reduced drug penetration into the spheroid core, the presence of a hypoxic and dormant cell population, and altered apoptotic signaling.

Endocrine Resistance (The Key Luminal Use Case): More importantly for HR+ cancer, the 3D spheroid platform has become an indispensable tool for investigating the mechanisms of acquired endocrine resistance (AER).

- Architecture-Driven Resistance: The 3D architecture alone can confer resistance. For example, large T-47D spheroids have been shown to spontaneously exhibit decreased ER expression and acquire resistance to 4-OHT (an active metabolite of tamoxifen), a phenomenon not observed in 2D culture(5).

- TME-Mediated Resistance: The spheroid model allows for the co-culture of cancer cells with components of the tumor microenvironment, such as bone marrow stromal cells (BMSCs). This is highly relevant, as bone is the primary site of Luminal A/B metastasis. Studies using 3D co-cultures of T-47D and MCF-7 spheroids with BMSCs demonstrated that the stromal cells induced hormone therapy resistance. Mechanistic investigation revealed this resistance was driven by TME-derived paracrine signals that activated IL-6-independent bypass signaling cascades, specifically the ERK and PI3K/Akt pathways, allowing the cancer cells to grow despite the ER-blockade(6).

- Metabolic Resistance: As noted, 3D spheroids demonstrate altered drug metabolism. For instance, studies examining CYP450 enzyme activity in MCF-7 spheroids found that this 3D organization changes the metabolic profile, which can impact the efficacy of drugs like tamoxifen, which requires metabolic activation(7).

This platform provides a clear “mechanism vs. prediction” dichotomy. Cell line-derived spheroids are excellent mechanistic tools. They allow researchers to isolate variables and answer specific biological questions (e.g., “What signaling pathway is activated when a T-47D cell is co-cultured with a bone stromal cell?”).

However, they are flawed as predictive tools. They are built from immortalized, homogenous cell lines that have undergone significant genetic drift and lack the intra-tumoral heterogeneity of a real patient’s tumor. They cannot answer the most important clinical question: “Will this specific patient’s tumor respond to this drug?” This limitation paved the way for the development of patient-derived models.

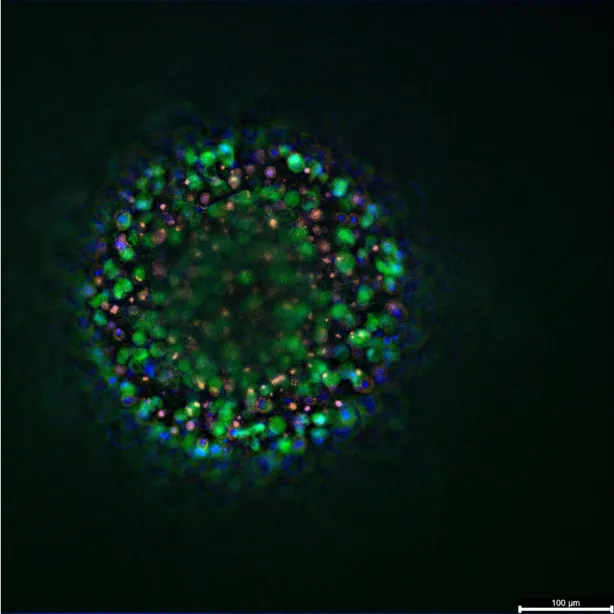

Patient-Derived Organoids (PDOs) for luminal A/B breast cancer

Patient-derived organoids represent a major advance in modeling luminal breast cancers. PDOs are established by taking tumor tissue (from surgery or biopsy) and culturing the cells in 3D matrices with growth factor–rich media, allowing tiny replicas of the tumor to grow. These organoids retain many characteristics of the original patient tumor, including the histopathological architecture and a mix of cell subpopulations. In hormone receptor-positive cases, the organoids typically preserve ER/PR expression, enabling studies of endocrine response. A key advantage of PDOs is their high success rate and rapid establishment compared to PDX mice: breast cancer organoids can often be grown within weeks, whereas PDX engraftment takes months and fails more frequently. Studies have shown that breast PDOs reflect the genomic landscape of the tumor to a significant extent, though there can be some drift (for example, organoids might be enriched in cancer stem-like cells or might lack some normal cells present in the original tumor). Overall, however, they provide an ex vivo avatar of an individual’s cancer, making them a powerful platform for precision medicine.

A good example of the different use case of these models is illustrated by Chen et al (2021)

Use in precision medicine: PDOs derived from luminal A/B breast cancers are being used to guide personalized therapy decisions. Chen et al. reported an influential study in which they generated organoid lines from patients with advanced breast cancer (including hormone receptor-positive cases) and performed high-throughput drug sensitivity screens. They tested a panel of 49 drugs (standard treatments and investigational agents) on each patient’s organoids to identify effective and ineffective drugs. The results demonstrated striking heterogeneity in drug responses between patients’ organoids. Importantly, the PDO drug responses correlated with clinical outcomes when those patients received therapy. In a follow-up of 13 patients, 100% of those whose treatment included at least one drug that the PDO model predicted to be sensitive achieved a favorable outcome (partial response, stable disease, or prolonged disease-free survival). In contrast, patients treated with drugs to which their organoids were resistant rapidly developed progressive disease. In summary, “all 13 patients exhibited response predictable by our drug sensitivity test,” underscoring that PDOs can recapitulate individual patients’ therapy responses. This case-series highlights how luminal breast cancer PDOs can be used as a real-time diagnostic platform to personalize treatment selection, for example choosing an alternate targeted agent if the organoid screen suggests resistance to standard endocrine therapy(8).

Drug screening and resistance mechanism studies: Beyond single-patient applications, PDO collections enable broader insights into luminal disease. Chen et al. expanded their breast PDO biobank to 76 lines and identified some common patterns: for instance, organoids were consistently resistant to the aromatase inhibitor formestane and to carboplatin, but were commonly sensitive to certain chemotherapies like doxorubicin and epirubicin (anthracyclines). Such data can inform which drugs tend to work (or not) in hormone-positive tumors ex vivo. They also observed that organoids from metastatic lesions (or heavily pre-treated tumors) showed broader drug resistance. For example, many metastasis-derived luminal PDOs were resistant to microtubule inhibitors (taxanes, vinca alkaloids) and EGFR inhibitors, and frequently resistant to the CDK4/6 inhibitor palbociclib. This aligns with clinical experience that metastatic or endocrine-resistant luminal cancers often have cross-resistance to multiple therapies. PDOs thus provide a model to investigate resistance mechanisms: researchers can analyze why a given luminal B organoid is non-responsive to hormone therapy or why it developed multidrug resistance. Genomic and transcriptomic profiling of PDOs that survived certain treatments can reveal resistance-associated mutations (e.g. ESR1 ligand-binding domain mutations causing aromatase inhibitor resistance) or pathway activations (e.g. upregulation of HER2 or PI3K signaling). Indeed, PDO studies have shed light on how treatment can select for resistant subclones – for example, comparing drug-treated versus treatment-naïve organoids in Chen’s study showed that prior therapies could imprint lasting resistance phenotypes, though interestingly the overall drug response profiles did not drastically differ between pre-treated and untreated groups.

Another use of luminal PDOs is in exploring drug combinations and novel therapies. Because organoids can be produced in substantial numbers, researchers can perform combination screens (testing, say, an endocrine therapy plus a PI3K inhibitor on an organoid that is endocrine-resistant). Chen et al. tested combining emerging drugs with standard agents on a subset of organoids to discover synergistic pairs. Furthermore, PDOs allow investigation of tumor biology under controlled conditions – for example, they can be co-cultured with patient-derived immune cells or fibroblasts to see how a luminal tumor organoid interacts with its microenvironment (though keeping stromal components alive in long-term organoid cultures is challenging). Summarizing, patient-derived organoids have opened new avenues for studying luminal A/B breast cancers: they serve as individualized test-beds for therapy (advancing precision oncology) and as models to uncover mechanisms of endocrine resistance, metastasis, and heterogeneity in hormone-receptor positive tumors. As protocols improve, PDOs from luminal tumors are expected to become even more routine, with the ultimate goal of testing a patient’s tumor against a panel of drugs before initiating treatment.

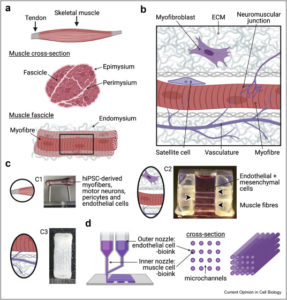

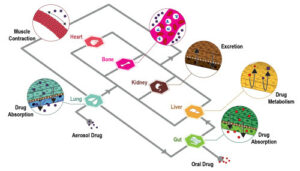

Tumor-on-a-chip platforms for Luminal A/B breast cancer

The latest frontier in modeling luminal breast cancer involves microfluidic “tumor-on-a-chip” systems. These platforms combine living cells with bioengineered microchannels to simulate key aspects of a tumor’s microenvironment (such as vascular blood flow, nutrient gradients, mechanical forces, and multi-cellular interactions) in a controlled in vitro device. Tumor-on-a-chip models build on the strengths of 3D cultures and add the dimension of fluid flow and compartmentalization, enabling researchers to replicate phenomena like blood circulation, immune cell trafficking, and organ-specific environments. For hormone-receptor positive breast cancers, several chip models have been developed using luminal cell lines (e.g. MCF-7, T47D) and even patient-derived cells, to investigate drug responses and tumor biology in ways not possible with static cultures.

Vascularized Tumor Chips and Drug Delivery: A major focus has been incorporating perfused micro-vessels into breast tumor models. Nashimoto et al. (2020) created a microfluidic device in which co-cultured MCF-7 luminal breast cancer cells and lung fibroblasts self-assemble into a spheroid, and adjacent microchannels are lined with human endothelial cells (HUVEC) to form perfusable capillaries(9). The endothelial cells sprouted new microvessels that grew towards the tumor spheroid, successfully vascularizing the 3D tumor tissue. This platform allowed the team to study drug delivery under flow conditions. Strikingly, they found that when chemotherapeutic drugs (e.g. 5-FU or doxorubicin) were delivered through the perfusable blood vessel analog, the usual dose-dependent tumor killing was blunted. The perfused spheroids were more drug-resistant compared to static (non-perfused) cultures. In other words, interstitial flow and vascular transport issues can abrogate chemo efficacy in the chip model, mirroring how inadequate drug penetration or washout in tumors may lead to therapy failure. This example highlights the value of tumor-on-chip systems: they recapitulate the in vivo pharmacokinetic context (nutrient and drug gradients, shear stress) that 3D static cultures lack. Other studies similarly showed that including a blood flow component alters tumor response. Pradhan et al. (2018) used a breast tumor chip with defined vessel geometries and observed reduced cytotoxic effect of drugs under flow vs static conditions. These vascularized luminal tumor chips are being used to test nanomedicine delivery, drug gradients, and even anti-angiogenic therapies in a realistic model of a perfused tumor(10).

Tumor–Stroma Interaction on Chips: Luminal breast cancers typically reside in an extensive stromal microenvironment of fibroblasts, extracellular matrix, and immune cells. Microfluidic chips enable precise co-culture of these elements. Gioiella et al. (2016) demonstrated an elegant breast tumor-on-chip that partitioned MCF-7 luminal tumor cells in one compartment and normal fibroblasts in an adjacent compartment, separated by an array of micropillars. The pillars allowed the two compartments to be in close contact (mimicking a tumor border) while preventing them from simply mixing. Using this model, Gioiella’s team observed that the fibroblasts became activated into cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) in response to signals from the neighboring luminal tumor cells. Specifically, fibroblasts upregulated αSMA (alpha-smooth muscle actin) and secreted factors like PDGF, indicating a shift to a myofibroblastic phenotype. This recapitulates the stromal activation seen in actual tumors and is valuable for studying how luminal cancer cells remodel their microenvironment. The same device was used to monitor tumor cell invasion: MCF-7 cells were seen migrating through the pillar interface into the stroma compartment over time, providing a visual model of local invasion. Thus, microfluidic platforms can capture the crosstalk between luminal tumor cells and stromal fibroblasts, something that static transwell co-cultures or spheroids with mixed cells cannot easily dissect with spatial resolution(11).

Immune Interaction and Immunotherapy Chips: Another cutting-edge application is integrating immune cells (such as T cells, NK cells, or macrophages) into tumor-on-chip models to study immuno-oncology in luminal breast cancer. Ayuso et al. (2021) reported a microfluidic model of ER+ breast cancer with an immune component. In their Science Advances study, an MCF-7 tumor spheroid was cultured in a central chamber, while a parallel channel lined with endothelial cells allowed controlled perfusion of immune cells (NK cells) into the tumor chamber. This setup mimics a scenario of NK cells extravasating from blood vessels into the tumor tissue. Ayuso et al. found that initially the NK cells could infiltrate and attack the tumor, but over several days the tumor-induced microenvironmental stress (nutrient depletion, low pH, hypoxia) caused the NK cells to become “exhausted” with their cytotoxic function gradually eroded. The NK cells in the chip lost their ability to kill cancer cells, leading to tumor escape, which mirrors the immune evasion observed in solid tumors in patients. Notably, the researchers tested potential interventions in this system: when they introduced an anti-PD-L1 checkpoint inhibitor or an IDO-1 inhibitor into the perfusion flow, the NK cell exhaustion was alleviated and tumor cell killing improved. This finding suggests that the chip can model not only the tumor–immune interaction but also predict responses to immunotherapies (in this case, showing that blocking PD-L1 can reinvigorate NK cells in an ER+ tumor context). Such immune-oncology-on-a-chip platforms are extremely valuable, as hormone-positive breast cancers generally have fewer tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes than, say, triple-negative breast cancers, and chips can help study how to boost immune responses in these “cold” tumors(12).

Metastasis and Organ-Specific Chips: Metastatic spread is the ultimate clinical challenge in breast cancer, and organ-on-chip technology is being applied to study steps of the metastatic cascade. Researchers have developed microfluidic models where breast cancer cells migrate through endothelial barriers (simulating intravasation/extravasation) or where two organ chambers are connected (for example, a breast tumor chamber and a bone-mimicking chamber to study bone metastasis seeding). In one example, a microfluidic device was used to examine the extravasation of MCF-7 cells vs. MDA-MB-231 cells through a 3D microvascular network under flow: luminal MCF-7 cells showed significantly less transmigration than the highly invasive triple-negative cells, consistent with their lower metastatic propensity. These metastasis-on-chip models allow observation of processes like cell invasion, angiogenesis, and colonization in real time within a perfused 3D environment. While much metastasis research focuses on aggressive subtypes, applying these models to luminal A/B cancer is useful for investigating phenomena such as dormancy (ER+ metastases can remain dormant for years) and the influence of hormone therapy on disseminated tumor cells.

Toward Patient-Derived Chips: Although most tumor-on-chip studies in breast cancer use established cell lines due to their reproducibility, there is a push to incorporate patient-derived tumor cells or organoids into chip devices. This could mean culturing a patient’s luminal tumor organoid in a microfluidic chip with continuous perfusion and immune cells from that patient – effectively a personalized “tumor microenvironment on a chip”. Early demonstrations of this concept are emerging, aiming to test individual patients’ tumor response to various conditions (e.g. how a patient’s organoid responds to immune attack by their own T-cells in a chip). Such approaches remain technically complex, but they foreshadow a future where patient-specific tumor-on-chips may be used for therapy testing with even greater realism.

References

- Harbeck N, Penault-Llorca F, Cortes J, Gnant M, Houssami N, Poortmans P, et al. Breast cancer. Nat Rev Dis Primer. 23 sept 2019;5(1):66.

- Clarke R, Jones BC, Sevigny CM, Hilakivi-Clarke LA, Sengupta S. Experimental models of endocrine responsive breast cancer: strengths, limitations, and use. Cancer Drug Resist [Internet]. 2021 [cité 6 nov 2025]; Disponible sur: https://www.oaepublish.com/articles/cdr.2021.33

- Holen I, Speirs V, Morrissey B, Blyth K. In vivo models in breast cancer research: progress, challenges and future directions. Dis Model Mech. 1 avr 2017;10(4):359‑71.

- Mangani S, Koutsakis C, Koletsis NE, Piperigkou Z, Franchi M, Götte M, et al. Spheroid-Based 3D Models to Decode Cell Function and Matrix Effectors in Breast Cancer. Cancers. 31 oct 2025;17(21):3512.

- Cheng GJ, Leung EY, Singleton DC. In vitro breast cancer models for studying mechanisms of resistance to endocrine therapy. Explor Target Anti-Tumor Ther. 1 juin 2022;297‑320.

- Dhimolea E, De Matos Simoes R, Kansara D, Weng X, Sharma S, Awate P, et al. Pleiotropic Mechanisms Drive Endocrine Resistance in the Three-Dimensional Bone Microenvironment. Cancer Res. 15 janv 2021;81(2):371‑83.

- Crispim D, Ramos C, Esteves F, Kranendonk M. The Adaptation of MCF-7 Breast Cancer Spheroids to the Chemotherapeutic Doxorubicin: The Dynamic Role of Phase I Drug Metabolizing Enzymes. Metabolites. 18 févr 2025;15(2):136.

- Chen P, Zhang X, Ding R, Yang L, Lyu X, Zeng J, et al. Patient‐Derived Organoids Can Guide Personalized‐Therapies for Patients with Advanced Breast Cancer. Adv Sci [Internet]. nov 2021 [cité 16 juill 2025];8(22). Disponible sur: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/advs.202101176

- Nashimoto Y, Okada R, Hanada S, Arima Y, Nishiyama K, Miura T, et al. Vascularized cancer on a chip: The effect of perfusion on growth and drug delivery of tumor spheroid. Biomaterials. janv 2020;229:119547.

- Pradhan S, Smith AM, Garson CJ, Hassani I, Seeto WJ, Pant K, et al. A Microvascularized Tumor-mimetic Platform for Assessing Anti-cancer Drug Efficacy. Sci Rep. 16 févr 2018;8(1):3171.

- Gioiella F, Urciuolo F, Imparato G, Brancato V, Netti PA. An Engineered Breast Cancer Model on a Chip to Replicate ECM‐Activation In Vitro during Tumor Progression. Adv Healthc Mater. déc 2016;5(23):3074‑84.

- Ayuso JM, Rehman S, Virumbrales-Munoz M, McMinn PH, Geiger P, Fitzgerald C, et al. Microfluidic tumor-on-a-chip model to evaluate the role of tumor environmental stress on NK cell exhaustion. Sci Adv [Internet]. 19 févr 2021 [cité 23 juill 2025];7(8). Disponible sur: https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.abc2331

FAQ

Luminal A and B subtypes are defined as hormone receptor-positive (HR+) disease. They are the most common forms, representing 70-80% of all breast cancer cases. These cancers are identified by their expression of the oestrogen receptor (ER) and progesterone receptor (PR). Luminal A is the more frequent type, found in 50-60% of cases. It is identified by low levels of the Ki-67 proliferation marker, indicating a slower-growing tumour with a generally good prognosis. Conversely, Luminal B is defined by a high Ki-67 level, meaning it has a higher proliferation rate. This subtype is considered more aggressive and is associated with a worse prognosis than Luminal A.

Treatment for HR+ breast cancer often uses endocrine therapies, such as tamoxifen or aromatase inhibitors, which target the tumour’s oestrogen dependency. While this approach is very effective at first, two central clinical difficulties remain. The first is acquired endocrine resistance, or AER. This occurs when tumours that originally responded to hormone blockade later return, frequently driven by complex bypass signalling pathways. The second major issue is late-stage metastatic recurrence. In this situation, patients may relapse in distant organs many years after finishing their therapy and being considered disease-free. These two events are the main causes of mortality for patients with Luminal A/B breast cancer.

Traditional research models, especially 2D cell lines like MCF-7 and T-47D, have been found to be insufficient for studying luminal breast cancer. These monolayer cultures are missing the foundational biological component of 3D architecture. This three-dimensional context is not just a physical difference; its absence means that important cell-cell and cell-ECM interactions are not re-established. As a result, 2D models fail to capture the physiological context of a tumour. They also lack genetic heterogeneity. Most importantly, these simple models often fail to properly model the key clinical problem of endocrine resistance, which is a primary reason for treatment failure in patients.

The development of 3D spheroid culture models was the first step away from 2D monolayers. Spheroids are typically generated from established cell lines, such as MCF-7 and T-47D. They are created using simple techniques designed to prevent the cells from adhering to plastic surfaces. A common method involves culturing the cells on ultra-low attachment (ULA) plates. When forced into suspension in this manner, the cells naturally aggregate. This process causes them to self-assemble into multicellular spheroids. These models are not meant to be patient-specific but are instead used as mechanistic tools to re-introduce 3D architecture.

The 3D spheroid platform is an indispensable tool for investigating the mechanisms of acquired endocrine resistance (AER) in HR+ cancer. Research has shown that the 3D architecture alone can induce resistance. For example, large T-47D spheroids were observed to spontaneously show decreased ER expression and acquire resistance to 4-OHT, an active metabolite of tamoxifen. This phenomenon was not seen in 2D culture. Spheroid models also permit the co-culture of cancer cells with components of the tumour microenvironment, such as bone marrow stromal cells (BMSCs). This is very relevant, as bone is the primary site of metastasis. Studies using these 3D co-cultures found that the stromal cells induced hormone therapy resistance by activating bypass signalling cascades, including the ERK and PI3K/Akt pathways.

Patient-derived organoids, or PDOs, represent a large improvement in modelling luminal breast cancers. Unlike spheroids made from homogenous cell lines, PDOs are established directly from patient tumour tissue obtained during surgery or biopsy. The cells are cultured within 3D matrices using growth factor-rich media. This process allows tiny replicas of the original tumour to grow. A main advantage of PDOs is their ability to retain many characteristics of the patient’s tumour, including its histopathological architecture and a mix of cell subpopulations. For HR+ cases, these organoids usually preserve ER and PR expression. PDOs also have a high success rate and can be established much faster than patient-derived xenografts (PDX), often within weeks.

PDOs derived from luminal A/B cancers are being used to help guide personalised therapy decisions. An influential study by Chen et al. generated organoid lines from patients with advanced breast cancer. The researchers then performed high-throughput drug sensitivity screens on each patient’s organoids using a panel of 49 drugs. This testing identified which drugs were effective and ineffective for that specific tumour. The results showed a strong correlation between the PDO drug responses and the clinical outcomes for those patients. In a follow-up of 13 patients, all who received a drug predicted to be sensitive by the PDO model achieved a favourable outcome. This work demonstrates how PDOs can be used as a real-time diagnostic platform to help select treatments, for example by choosing an alternate targeted agent if the screen suggests resistance.

Microfluidic “tumour-on-a-chip” systems are a new frontier in modelling luminal breast cancer. These platforms are controlled in vitro devices that combine living cells with bioengineered microchannels. Their purpose is to simulate important aspects of a tumour’s microenvironment. These aspects include vascular blood flow, nutrient gradients, mechanical forces, and interactions between different cell types. Tumour-on-a-chip models build upon the strengths of 3D cultures. They add the dimensions of fluid flow and compartmentalisation, which are missing from static cultures. This allows researchers to replicate phenomena such as blood circulation and immune cell trafficking in a more realistic way.

A major focus of tumour-on-a-chip systems has been to incorporate perfused micro-vessels. For example, Nashimoto et al. created a microfluidic device where MCF-7 luminal cancer cells were co-cultured with endothelial cells to form perfusable capillaries. This platform allowed the team to study drug delivery under flow conditions. They found that when chemotherapeutic drugs like 5-FU or doxorubicin were delivered through the artificial blood vessel, the expected dose-dependent tumour killing was blunted. The perfused spheroids were more drug-resistant than static cultures. This result mirrors how inadequate drug penetration or washout within a real tumour can lead to therapy failure. It shows the benefit of recreating the in vivo pharmacokinetic context, such as flow and gradients, which static 3D cultures lack.

Yes, integrating immune cells into tumour-on-a-chip models is a developing application for studying immuno-oncology in luminal breast cancer. Ayuso et al. reported a microfluidic model of ER+ breast cancer where an MCF-7 spheroid was cultured in one chamber. A parallel channel lined with endothelial cells allowed for the controlled perfusion of NK immune cells. This setup mimics NK cells moving from blood vessels into the tumour tissue. The researchers observed that the NK cells initially attacked the tumour but became “exhausted” over several days due to the tumour-induced microenvironmental stress, such as hypoxia and low pH. The NK cells lost their killing ability, leading to tumour escape. This system can also test immunotherapies; introducing an anti-PD-L1 checkpoint inhibitor was found to lessen the NK cell exhaustion and improve tumour cell killing.