Temperature control to track viral entry during live-cell imaging

Our temperature controller allows you to precisely control the temperature of your host cells, or switch temperature from 5 to 45C in seconds and thermally control viral entry and transport inside the cells, take a tour!

Mechanisms of viral entry

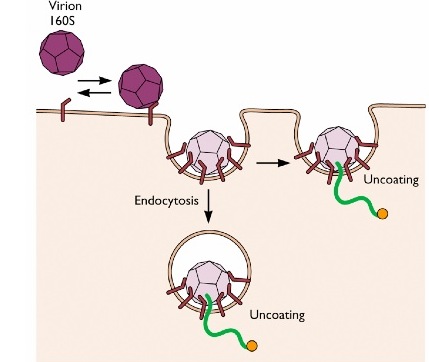

Viral infection begins with the attachment of viral particles to the host cell membrane. This is a complex process during which viral capsid proteins bind to receptors at the cell membrane. These receptors can be proteins, carbohydrates or lipids. The viral particle is then internalized by endocytosis or by membrane fusion with the host cell. The mechanism of entry depends on the type of viruses namely enveloped or non enveloped viruses.

Ultra fast temperature shift device for in vitro experiments under microscopy

Viral entry of non-enveloped viruses

Non-enveloped viruses such as Influenza virus or vesicular stomatitis viruses enter the cell through endocytosis, using both clathrin dependent or clathrin independent pathways. Poliovirus, a non-enveloped virus, uses two alternatives strategies to enter the cell. The virus can be endocytosed :the hydrophobic part of the viral protein VP1 will insert inside the cell membrane of the endocytosed vesicles and form a pore to allow the penetration of the viral RNA. In the second strategy, the virus attaches to the cell membrane and directly releases its RNA material inside the cell.

Viral entry of non-enveloped viruses

Enveloped viruses, such as HIV, MLV or Ebola virus, enter the cells via membrane fusion. First, viruses dock to the cells; the binding of specific viral proteins to cell membrane receptors ensures the bridging of virus and host membranes. Subsequently both outer layer membranes of virus and host will fuse and the capsid or viral genome will be release inside the host cytoplasm. Since fusion is the first step towards cell infection, finding anti-fusion agents is a major area of research in pharmaceutics. An exhaustive lists of fusion proteins and entry mechanisms can be found the excellent principles of virology book (Flint et al., 2009).

Studying viral entry with live cell imaging

Key questions arise from studying viral entry : which viral and host proteins participate in viral entry ? What are the entry mechanisms ? What are the subsequent cytoplasmic transport mechanisms ? How to inhibit virus entry ?

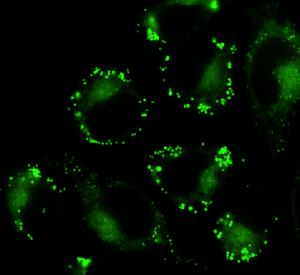

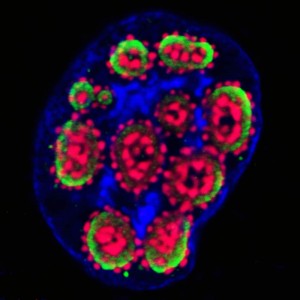

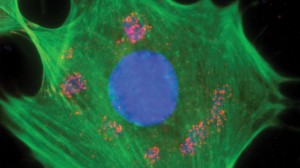

Live-cell imaging allows to track single viral particle as it enters and traffic inside the host cell. The use of fluorescent proteins, fluorescent dyes such as amino-reactive dyes or lipophilic dyes enables the visualization of viral particles (Ayala-Nunez et al., 2011), however labeling can affect viral infectivity and the correct amount of dye has to be determined for each type of viruses-host studies. Viral entry into cells can be followed by fluorescently labeling the viral membrane, the viral content or the viral core (Hulme and Hope, 2014). If viral membrane is labeled, fusion events will consist of a disappearance of fluorescence, however if viral content is also labeled it will then be possible to follow the transport of viral particles inside the cell.

Temperature control of viral entry with CherryTemp

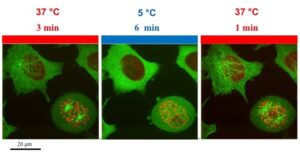

Viral entry into the cell is temperature dependent. In 2007, Brandenburg and colleagues used live cell imaging to precisely determine poliovirus entry mechanism into cells. By performing a series of experiments at 37C and 12C, they could determine that at 12C, poliovirus could no longer infect the cell, revealing that it was using endocytosis mechanism to penetrate. These types of experiments require a specific microscope setting with a thermally controlled environment to keep the cell warm during the manipulation. One caveat is the possibility to rapidly switch temperature to control both viral entry and viral transport inside the cells.

With our ultra-fast shift temperature controller for live cells imaging, you can very precisely and very quickly change temperatures, it goes from 5C to 45C in seconds. You can trigger viral infection by switching from 4C to 37C, pause viral entry by switching in seconds to 12C, acquire high-resolution images and resume viral entry process. It is a plug and play system and fits on any microscope setting.

References

- Ayala-Nuñez NV, Wilschut J, JM Smit, Monitoring virus entry into living cells using DiD-labeled dengue virus particles, Methods, 2011

- Flint SJ , Enquist LW, Racaniello VR, and Skalka AM, principles of virology, asm press, 2009

- Hulme AE. and Hope TJ., Live Cell Imaging of Retroviral Entry, Annu. Rev. Virol, 2014

- Brandenburg B, Lee LY, Lakadamyali M, Rust MJ , Zhuang X , Hogle JM Imaging poliovirus entry in live cells, PLoS Biol, 2007

- Webb S, Alive and in focus, The scientist, 2012

- S. Ben-Aroya, X. Pan, JD. Boeke, and P. Hieter, Making temperature-sensitive mutants, Methods Enzymol. 2010

FAQ

Viral infection is initiated by the attachment of viral particles to the host cell membrane. This attachment is an intricate process. During this step, viral capsid proteins bind to specific receptors located on the cell membrane. These receptors vary in composition; they can be proteins, carbohydrates, or lipids. After attachment is complete, the viral particle is then internalised by the cell. One of two main methods is used for this internalisation. The first is endocytosis, where the cell takes in the particle. The second is membrane fusion, where the virus merges with the host cell’s membrane. The specific entry method that is used is dependent on the type of virus. In particular, the method depends on whether the virus is an enveloped or a non-enveloped virus.

The method of entry is different for non-enveloped and enveloped viruses. Non-enveloped viruses, such as influenza, typically enter the cell through endocytosis. The poliovirus, which is a non-enveloped virus, can use two different strategies. It can be endocytosed, after which a viral protein forms a pore in the vesicle membrane to allow the viral RNA to penetrate. Alternatively, the poliovirus can attach to the cell membrane and release its RNA material directly into the cell. Enveloped viruses, like HIV or Ebola virus, use membrane fusion to enter cells. First, the viruses dock to the host cell. Specific viral proteins bind to membrane receptors, which bridges the two membranes. Following this, the outer layer membranes of the virus and the host cell fuse together. The capsid or viral genome is then released into the host’s cytoplasm.

The entry of viruses into cells can be studied by using fluorescent labels on different parts of the virus. The viral membrane, the viral content, or the viral core can be labelled. Observations of single viral particles as they enter and move inside the host cell are made possible with microscopy of living cells. The visualisation of viral particles is accomplished through the use of fluorescent proteins or different types of dyes. Examples of these dyes include amino-reactive dyes or lipophilic dyes. A consideration is that the labelling process itself can affect the infectivity of the virus. The correct amount of dye must be determined for each specific study. The chosen labelling strategy also affects what can be observed. For instance, if the viral membrane is labelled, fusion events will be seen as a disappearance of the fluorescence. If the viral content is also labelled, the transport of the viral particles inside the cell can then be followed after fusion.

The process of a virus entering a cell is known to be dependent on temperature. This dependency can be used in experiments to determine the method of entry. For example, a study in 2007 on the poliovirus was conducted using observation of living cells. A series of experiments were performed at 37°C and 12°C. It was determined by the researchers that poliovirus could no longer infect the cell at 12°C. This finding revealed that the virus was using an endocytosis mechanism to get inside the cell. Experiments of this type require a specific microscope setting. The setting must include a thermally controlled environment to maintain cell temperature during manipulations. The ability to rapidly switch the temperature is noted as a way to control both the entry of the virus and its subsequent transport inside the cells. For instance, infection can be started by switching from 4°C to 37°C, or paused by switching to 12°C.